Key Takeaways

With irrational investor enthusiasm over the metaverse accelerating, what is metaverse-type business logic?"

It is still not yet clear what metaverse-type convergence will look like operationally and strategically.

Minecraft and Axie Infinity are online games considered to be existing "metaverse" business models

Dotdash is a helpful example here: for all its sophistication around user intent, it does not pursue more robust models like Minecraft's or Axie's.

Minecraft, Axie Infinity and Dotdash all try to hyperserve user interest: where Dotdash's model ends is where metaverse business models begin.

Irrational investor enthusiasm for the metaverse is only accelerating, and I am only becoming more skeptical of that outcome.

In Friday Mailing #50: Robert Iger, Mark Zuckerberg & Vision, I compared Zuckerberg's vision with former Disney CEO Robert Iger's vision for Disney streaming:

But what bothers me is the complexity in [Zuckerberg's] vision, even if the vision is also about Meta focusing on simplicity through “the interconnected nature of his company’s products”. Iger tells us he held a video iPod in 2005 and had a concrete “vision” of where content distribution was headed. I’m not sure where Zuckerberg thinks the metaverse is headed, but in both listening to him and reading interviews with him, he believes “the metaverse is the next chapter of the Internet”.

I lean more towards Iger’s narrower thinking here: either the metaverse is the next evolution and iteration of a familiar business model, or it isn’t.

Nobody seems to know for sure where the metaverse is headed beyond the broad brushstrokes of permutations of offerings across livestreaming, gaming, VR, AR, Creator Economy, NFTs, crypto, and the “distributed retail” future for e-commerce.

That is why this essay on the metaverse from writer Clive Thompson offers a helpful angle:

The truth is, a thriving metaverse already exists. It’s incredibly high-functioning, with millions of people immersed in it for hours a day. In this metaverse, people have built uncountable custom worlds, and generated god knows how many profitable businesses and six-figure careers. Yet this terrain looks absolutely nothing the like one Zuckerberg showed off.It’s Minecraft, of course.

So one answer we have is Minecraft. Take-Two CEO Strauss Zelnick made a similar argument that GTA Online, Red Dead Online, and NBA2K's online world are all existing metaverses to GamesBeat.

Another answer is Axie Infinity, a crypto game in which you breed creatures called Axies and send them into battle against one another. Rex Woodbury wrote an essay on the economics of Axie on his Substack, Digital Native:

...1) Axie is probably the most important on-ramp to crypto in the world right now, and 2) because as more workers find work in the metaverse, we often overlook how complex these economies are. Digital economies may be disguised within games—in Axie’s case, within a colorful world of cute, quirky creatures—but they’re deceptively intricate. We can learn a lot from these early digital economies about the future of internet-native work in the post-Covid era.

The point of both examples is not to predict what the metaverse will look like - I remain deeply skeptical of the concept as a universal outcome.

Rather they help to suss out the signals of metaverse-type business logic from the growing irrational enthusiasm for the metaverse, as I did in Member Mailing #273: MGM Resorts M life "Convergence" vs. "Metaverse" Convergence (August):

There is now more of an overarching business logic to the concept in 2021 than in 1992 with both cloud computing and DTC business models driving the gaming industry towards “Metaverse”-type models (e.g., Epic Games). But, beyond gaming there is still not much business substance to it, especially in legacy media. The appeal of the concept is convergence: how will gaming, music, streaming, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, and e-commerce drive the convergence of digital and physical worlds, private and public networks/experiences, and open and closed platforms?More importantly, what will this convergence look like operationally and strategically?

Dotdash, which monetizes “intent-driven”, “need to know” premium content offers a helpful lens. Dotdash has invested more heavily than legacy media companies into its SEO-focused approach to engaging and monetizing user intent. Metaverse business models share more with Dotdash than they do with legacy media impression-driven business models.

Minecraft and Axie both have more sophisticated offerings built around user intent that help us to understand the metaverse chatter better, and give us valuable signals of what a viable metaverse business model may look like.

Thompson on Minecraft

Minecraft is a sandbox game with 141MM monthly active users (MAUs), and its Wikipedia entry describes the gameplay as:

In Minecraft, players explore a blocky, procedurally generated 3D world with virtually infinite terrain, and may discover and extract raw materials, crafttools and items, and build structures or earthworks. Depending on game mode, players can fight computer-controlled mobs, as well as cooperate with or compete against other players in the same world. Game modes include a survival mode, in which players must acquire resources to build the world and maintain health, and a creative mode, where players have unlimited resources and access to flight. Players can modify the game to create new gameplay mechanics, items, and assets.

Thompson offers seven rationales for why Minecraft reflects this convergence:

It’s decentralized — nobody owns *the* Minecraft metaverse

Minecraft is incredibly immersive — yet uses low-fi tech

Minecraft *requires* you to be creative

It’s open and hackable

Minecraft is glitchy

There’s a reason to be there

It spawns tons of economic activity

#2 and #5 are most interesting to me because they reinforce a key lesson of the past 15 years of Web 2.0: less is more.

Both Google and Facebook built monopolies with simple interfaces but robust data-driven back-ends. YouTube still, by and large, leverages many of its original User Experience (UX) design choices. All are at a scale that dwarfs legacy media businesses over the past 15 years, which have bet on interfaces that please advertisers more than customers.

Thompson sums this dynamic up best:

A really interesting metaverse — one in which you’d want to spent hours, days, years — is messy. It’s not the Stepford airport lounge that Zuckerberg seems determined to build.

If there is one general truism of Facebook's and Google's attempts at algorithmically engaging its users worldwide, it's the adjective "messy". Zuckerberg's glossy, idealistic Meta presentation was the opposite of "messy".

This points to two other rationales of Thompson's to flag. First, "there's a reason to be there" for users:

People play Minecraft because it’s a game. It was designed for a specific purpose — to give you an environment with blocks you could recombine, so that you could engage in a “survival” challenge (build things to keep yourself alive while monsters attack) or simply to build Lego-style creations (in the no-monsters “creative” mode).Because it’s a game, people know why they’re using it, when they use Minecraft. There’s a reason to be there: to play the game! Once people showed up, they discovered Minecraft was open-ended enough that they could do all sorts of things with it — hang out with friends, build their own sports and combat, create cool machines, record animated series on YouTube, etc. But they wouldn’t have arrived in the first place if there wasn’t a game to play. (A similar thing can be said of World of Warcraft or dozens of other online multiplayer games that people use as hangouts with their far-flung friends.)

Minecraft may not be premium, but it is intent-driven.

Second, Minecraft "spawns tons of economic activity":

People make loads of money off Minecraft and its culture. Some build server-worlds so enticing people pay to hang out. Others become talented Minecraft creators, then amass huge and profitable followings on YouTube or Twitch or Discord teaching their skills. Some become elite players in the many forms of gaming that have built up around Minecraft — games which, I should point out, weren’t invented by Mojang; they were invented by folks who inhabit the gameworld. Are you into NFTs? People are already devising how to graft that onto Minecraft servers.

Minecraft rewards intent by offering additional user-created marketplaces with creativity and entrepreneurial savvy, and at an extraordinary scale.

Daring Fireball's John Gruber added this observation about the value of Minecraft being a closed system and not open-source:

A closed system that encourages and enables a rich amount of user-hackery within a set of reasonable constraints is almost certainly more fun and rewarding than an anything-goes free-for-all.

Woodbury on Axie Infinity

Axie Infinity is a crypto game with 2MM daily users in which you breed creatures called Axies and send them into battle against one another.

You need three Axies—three creatures—to play the game. You spend money to buy your Axies (or Yield Guild lends you Axies so you can start playing, since each Axie currently costs ~$200), and then you play either Adventure Mode or Arena Mode. If you win, you’re awarded SLP. Using Uniswap or Binance, you can convert your SLP into ETH and then into dollars. That’s how you make real-world money playing the game.

SLP is short for Small Love Potion, which is the currency for Axie’s economy.

Rex Woodbury is focused on the metaverse implications of Axie Infinity, and argues the economics of Axie are important because:

1) Axie is probably the most important on-ramp to crypto in the world right now, and 2) because as more workers find work in the metaverse, we often overlook how complex these economies are. Digital economies may be disguised within games—in Axie’s case, within a colorful world of cute, quirky creatures—but they’re deceptively intricate.

Axie Infinity is effectively a means for users to make a living (Woodbury gives the example of a Venezuelan woman who earned more playing Axie Infinity for just a few days than she could earn working her previous job for a full month).

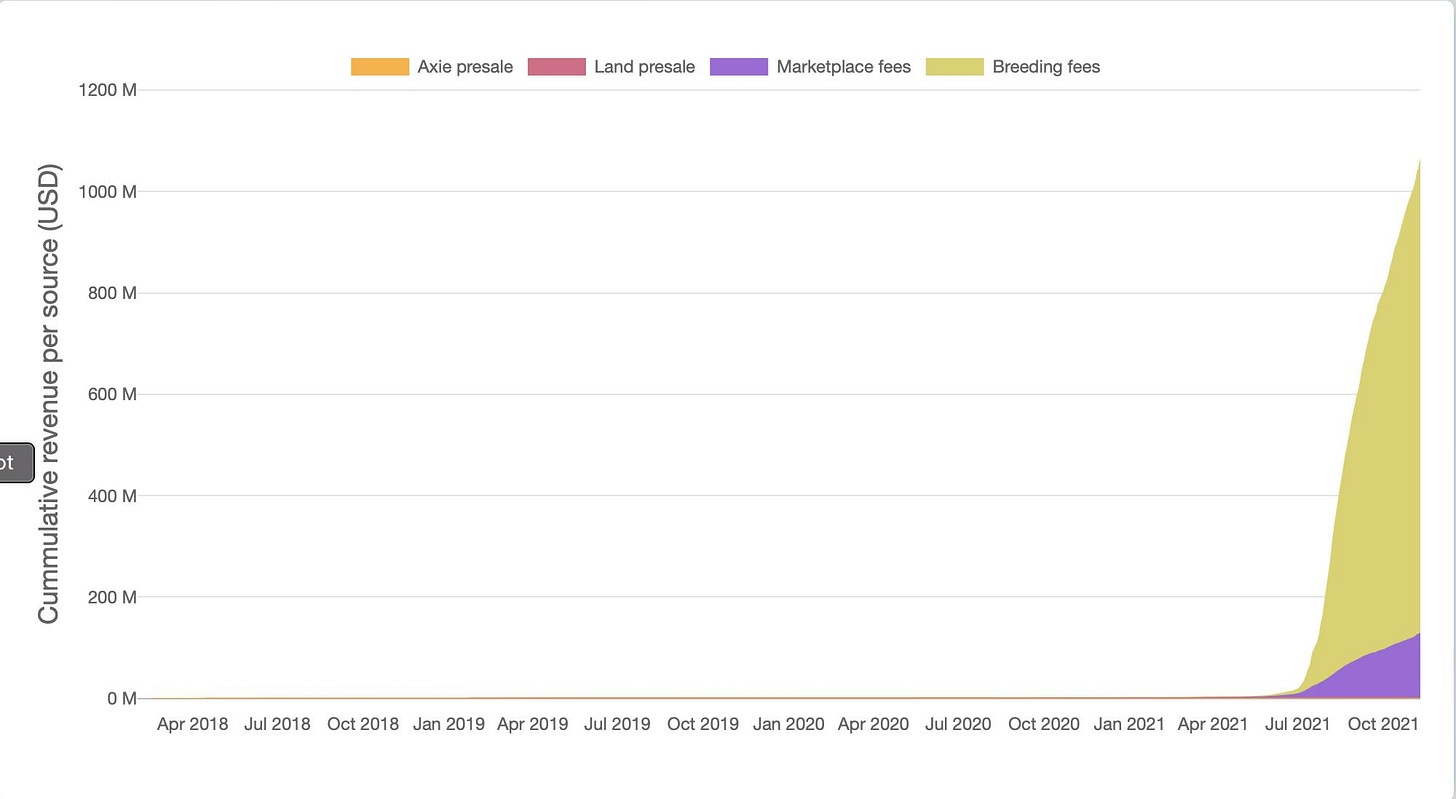

The intent for Axie users is not only to play but to make money in a centrally managed online economy. Axie is on track to book $1B in revenue in 2021.

That explosion in growth came on April 28th:

when the game switched from the Ethereum blockchain to the Ronin sidechain. Before the switch, players had to pay high transaction fees on Ethereum, which limited who could afford to play. Ronin eliminated those fees. Along with switching to Ronin, Axie integrated Ramp.Network, a fiat-to-crypto platform—in other words, now people could buy ETH using their credit card. This opened the floodgates to people who could buy Axies on the marketplace and start playing the game

According to Woodbury:

On the surface, Axie seems like a fun game full of cartoonish creatures. But underneath, it’s a vibrant and robust world that is reimagining how we interact and earn online.

Why User Intent Matters

I write often about DotDash because it is a media company that has succeeded in monetizing “intent-driven”, “need to know” premium content. It has a broader business logic of “Brand-Driven Intent Audiences Are the Most Valuable” (from its Dotdash Meredith merger presentation).

Dotdash succeeds because it iterates its business and content production models into serving search behaviors and other intent-driven digital behaviors. There was a slightly more detailed explanation about Dotdash's model provided by CEO Neil Vogel in the IAC Q3 2021 earnings call than has been provided, to date:

We're very focused on search because we're very focused on algorithms. And if you're going to be a publisher today or if you're going to be in consumer Internet in any way, you're going to be in travel, you're going to be in anything, algorithms are going to be between you and your users. And what -- the algorithms we care about are the algorithms that care about where they send users.So that means Google, that means Pinterest, that means Apple News, that means Flipboard. That means -- sort of like the different algorithms within Google, we care a lot about. So when we look at a new site, consistent with what we've done with other things we bought, it's very, very comprehensive. And we are as concerned with the oldest piece of content as you are with the newest piece of content. So because a user doesn't care and an algorithm doesn't care, they just want to know what's on that domain and what is it covering. Is it the best thing?And that's our focus.

He then adds an interesting caveat at the end of his answer:

...one of the things we say, which we stole from another publisher, is like not all of our content that we have makes us money, and we don't care about that.But all of it supports the content that makes us money, which means that if you're going to have a health domain, there's obviously going to be some topics that are very big and some topics that are very small. The small topics have to be treated with the respect and the care of the big topics because the person who uses that or the advertiser that sees it, it doesn't matter to them that it's a small topic. It matters to them that that's their topic. And we look at all domains that way.

Vogel's point is simple: user intent matters most, and Dotdash understanding and evolving its content offerings around user intent may matter even more.

Minecraft's and Axie's metaverse business logic takes a similar path to Dotdash in going deep into understanding and serving user intent. But both go deeper in their relationships with their users and in more dynamic directions, like crypto, e-commerce, and creator economy models.

That's what metaverse business logic through the lens of user intent looks like.

Conclusion

Metaverse business logic is multivariable to an extreme. so focusing on something like user intent seems reductive to the point of absurdity.

But, if I were to boil down the significance of user intent in emerging metaverse business logic, it is two-fold:

understanding user intent has been the difference between success and extraordinary success in legacy media and streaming (Mic Drop #41: Disney+ Needs Bundles (& Perhaps Personalization) to Scale), and

metaverse business logic offers more mechanisms to reward, further incentivize and monetize user intent than legacy digital media offerings.

I have written about the first in my pieces on Dotdash. I wrote about the second in Member Mailing #273: MGM Resorts M life "Convergence" vs. "Metaverse" Convergence back in August. I made a narrower argument about the growing importance of Customer Data Platforms (CDPs) in that piece.

But even in that essay, I concluded:

Whether it is Amperity or another CDP, the point is that MGM Resorts has taken a highly technical, AI-driven solution and re-imagined its online and offline consumer relationships. It did not go big picture or abstract in the pursuit of conceptual objectives.MGM Resorts’ initial success in solving for its pain points may not inspire the marketplace’s imagination like the “Metaverse”, but it is valuable precedent.

A CDP can be considered a key operational step towards centralizing all information around user intent across sales channels.

So, better understanding whether a metaverse-logic business model is focused on solving for user intent seems to be a valuable first step for filtering signal from the noise in the "metaverse".

Minecraft, Axie Infinity and Dotdash all try to hyperserve user interest. But where Dotdash's model ends seems to be where metaverse business models begin.