PARQOR is the handbook every media and technology executive needs to navigate the seismic shifts underway in the media business. Through in-depth analysis from a network of senior media and tech leaders, Andrew Rosen cuts through what's happening, highlights what it means and suggests where you should go next.

In Q4 2022, PARQOR will be focusing on four trends: this essay is on a trend that hits all four.

I think there are three essays to be written on the topic. One is an essay on how this subtext has been playing out in recent market news (below).

The second will be an essay that highlights how this theme is playing out within and across each of the four themes PARQOR is writing about in Q4 2022. I’m going to write that over the next few weeks.

The third is an opinion piece I’m planning for The Information next week diving into how most of legacy media simply cannot bring itself to move beyond 22 minutes or 44 minutes as a format, and the market implications of that.

I'm keen to connect with subscribers and readers on a free trial to learn more about you need from a subscription service. Click here to set up an appointment: https://calendly.com/andrew_parqor/30min

Towards the end of Mark Bergen’s new book on YouTube, “Like, Comment, Subscribe”, he shares the story of a YouTuber named MatPat who documented changes made by Google to YouTube’s recommendation algorithm in 2015.

In May 2015, videos devoted to “Minecraft” game play had previously occupied 14 slots on YouTube’s version of its home page for people not signed in with Google accounts, and by September 2015 they occupied none. YouTube had “tilted the algorithm to show videos that ‘everybody from my daughter to my mom might like” because it believed it “needed a more broadly appealing welcome mat”. “Minecraft” game play videos - which has been vital to driving engagement - were now too narrowly targeted. Traffic on Minecraft channels subsequently crashed, and it was unclear why. Bergen writes:

Had the audience tired of these? Maybe. Maybe not. "Humans watch what's presented to them," MatPat observed in his video. "What's right in front of their faces."

I love this quote because it succinctly captures a dynamic I wrote about in August: “In a world where YouTube (135MM connected TV (CTV) viewers per month in the U.S.) and TikTok (~80MM monthly active users in the U.S.), increasingly are capturing consumer attention - and advertisers are shifting spend accordingly - the traditional linear TV definition of ‘premium content’ matters less and less.”

I have yet to read or hear anyone define premium content as “what's right in front of [consumer] faces”. You hear or read it more as “attention economy” logic: basically, Netflix telling shareholders that it competes for attention with Epic Games’ Fortnite or linear TV. But I like this definition because it’s a bit meatier than the premise of the attention economy - basically, turning attention into money - and meatier than Netflix’s “if they don’t choose us then they choose something else”.

It’s a ruthlessly simple premise: if content has made its way to be presented to an audience, it is premium content.

Key Takeaway

If we agree that "premium" content is "content that has made its way to be presented to an audience", relevance and not production value now defines what makes content "premium" in streaming.

Total words: 2,400

Total time reading: 10 minutes

If you think about it, that was and still is linear distribution’s value to consumers and advertisers: Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs) provide the pipes, the cable boxes and the User Interfaces to present content on TVs to users. Users turn on a TV and/or a cable box and, boom, there’s instantly something to watch. Change the channel, and there's instantly something else present to watch.

Cable, telco and satellite providers ended the quarter with a combined, estimated 85.1 million video subscribers. So 85MM have the ability to consume what is right in front of their faces as presented by an Electronic Programming Guide (EPG). The formats are predictable: TV series that are 22 minutes of programming and 8 minutes of ads, or 44 minutes of programming and 16 minutes of ads, and movies that can last anywhere from 1.5 to 2.5 hours without ads, and longer when served with ads.

The conversation gets messy when we start talking about what's being presented to users on TVs outside of linear. An easy and familiar example that helps to cut through this mess is CTV:

There are over 1.3B connected TV devices worldwide and 500MM in the U.S., alone. Those households with a broadband connection and a Connected TV device (we can assume 120MM) are presented with content either:

In the TV OS platform, or

Directly within a streaming app.

1. In the TV OS platform

Back in July, I wrote about how Smart TV user interfaces (UI) and user experiences (UX) create “a lot of friction” between the streaming consumer and a sports broadcast. They also create “a lot of friction” between the user and content with the apps, more generally.

That’s the inherent problem outside of an app: “what’s right in front of their faces” in that CTV UX/UI is a selection of apps . Some TV OSes like Apple TV OS, Samsung or Comcast’s Xfinity do curate “what to watch” titles from within services and recommend them to the user (image below). But generally speaking, what is presented to consumers in a TV OS isn’t always content to watch.

Rather, it’s a choice of apps. As I tweeted yesterday in an exchange with CuriosityStream’s Chief Product Officer Devin Emery, I can finish an HBO show and then choose between YouTube or Disney+ or Netflix. "Good" doesn't matter. It's what captures my attention that matters.

The reasons why a user chooses an app within a TV OS has little to nothing to do with the content in front of them, because there is no content in front of them. They may be aware of content in the app, but no app displays the content within it. Rather, it has more to do with a long list of variables that include but are not limited to price, brand awareness or awareness of a specific show, or simply curiosity.

Once the user has clicked on the app, then they are presented with choices of content to consumer. Meaning, something about the app’s ability to drive both click-thru and viewing makes the content within that app “premium” in streaming. But nothing in the CTV interface before the consumer entering the app makes the app’s content “premium”.

So, the things we have come to believe are premium about the content over many decades - production value, lighting, screenwriting, directing, editing, costumes, set design, performances of actors - they aren’t what make content “premium” in streaming.

2. In-App - Algorithm vs. No Algorithm

Once the user is in the app, they are either presented with content that’s been curated by an algorithm, or curated by the company that owns the service based on its business objectives (e.g., promoting a show in the top banner or a sports match).

YouTube is the best example of curation by an algorithm: users of the YouTube CTV app are recommended content based on a recommendation algorithm, they are served ads by an algorithm, and their comments are moderated by an algorithm (and the messes those algorithms have created are covered in Mark Bergen’s “Like, Comment, Subscribe”).

The Minecraft example, above, was content presented to users who were not logged into YouTube in 2015. Effectively, what is “presented” to the user is recommended by the algorithm based on what it knows about you, and if it doesn’t know you, it is recommended “a more broadly appealing welcome mat” of content that meets YouTube’s business objective.

So, it’s reasonable to assume that what’s right in front of the faces of the user within an algorithm-driven app like YouTube, TikTok, Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime Video or HBO Max is a mix of:

The business objectives of the service, and

What the algorithm recommends based on what it knows about the user.

Of course not all of the content that reaches a user on YouTube is in itself premium - Bergen writes at length about the havoc that hate speech and conspiracy videos have wreaked on YouTube's and broader global society after being recommended repeatedly to viewers by YouTube's algorithm. But, the fact that it is presented to the user in the YouTube interface makes it more relevant to the user and therefore more likely to be watched. That makes YouTube content “premium".

Apps without an algorithm like Paramount+ and Peacock, and smaller apps without an algorithm like AMC+ and discovery+, deliver content primarily based on the business objectives of the service. They might have some personalization (e.g., “watch again” to watch a show again” or “recently watched”), but generally they deliver libraries of content that were premium in linear. But now that they can't be surfaced by an algorithm as relevant, they are no longer premium.

Putting functionality like search or even marketing aside (YouTube runs clickable ads, Roku helps apps market shows within its interface), the point is that the streaming era has set up the home page of an app to determine what makes content premium more than the production value of the content itself.

It seems counterintuitive to write, but YouTube’s homepage may be the acme of premium content simply because it is able to customize itself for 135MM connected TV device users who either have accounts or don’t have YouTube accounts.

What is the business of premium?

As cord-cutting accelerates, what is the business of media if an app’s home page is more valuable than the content itself? Why have expensive production budgets for TV shows or movies when ultimately production value matters less than what is being presented when the user logs in?

IAB Executive Chairman Randall Rothenberg offered a good framework for this in a Twitter response to Monday’s essay. He made two interesting points:

“Hollywood Economy denizens believe that most formats are “fixed” in human nature. Which is why formats like 130-min. feature film, 30-min sitcom, 13-episode streaming “season” evolve so slowly. But in fact, people consume far more ecumenically than industrially.”

“This is central to why the Internet continues to confuse business professionals nearly 30 years after the Mosaic browser. It allows vast customization potential, in an economy premised for 200 years on industrial standardization.”

Monday’s essay on YouTube Shorts as a competitive threat to Netflix had a perfect example of his first point, and it was from the newsletter ICYMI by Lia Haberman: "The Shorts algorithm and the long-form algorithm will “speak to each other.” So someone who watches a Shorts video on a particular topic could be served up long-form content around the same topic."

Meaning, the YouTube CTV consumer is now going to be format agnostic, if they are not already. Production value will matter increasingly less to YouTube consumption than relevance of content and the ability to dive deeper into YouTube based on its algorithmic recommendations will matter more.

TikTok’s move into the CTV space will only reinforce these trends. As TikTok’s rapid emergence over the past six years in mobile has proven - over 1B users worldwide, and 136.5MM users in the U.S. - there is no single format of content that *needs* to reach audiences on the Internet. Production value means little. Rather, what is presented and to whom matters most, and that has been TikTok’s defensible value proposition.

Rothenberg’s second point is partially reflected by legacy media companies who have not built algorithmic services (NBCU’s Peacock, Paramount+, Starz). All are betting on the power of legacy media productions and marketing for those productions to drive eyeballs to the homepage of an app. Those productions are expensive because their budgets assume distribution at scale on linear and streaming, and the marketplace is moving towards more diverse consumption behaviors that value production less.

Example: "The Office"

There’s also the example of NBCUniversal’s $500MM investment in “The Office”, which surfaced in an anecdote told by B.J. Novak - who starred as Ryan Howard in “The Office - to Recode’s Peter Kafka on the Recode Media podcast back in August. “The Office” used to be Nielsen’s most streamed show in the U.S. in 2020 (57.1MM minutes streamed).

At about 32 minutes in, Kafka asks him if he could feel the difference after “The Office” left Netflix, if the show now feels “less popular?” Novak answered:

“I thought it would feel less popular but the weird thing is, when I ask teenagers who say “We love The Office!”, I say “Do you watch it on Peacock?” and more often I hear “No we watch it on YouTube.” And people will watch highlight reels of it and consider that the show.”

He also told the story of a teenager at a children’s hospital he was visiting who was excited to meet him, and when he asked her what her favorite episode of “The Office” was, he recalls she responded: ”’Well I really know you from the memes… ‘ and she meant it. I was from ‘The you writing in the notepad meme, and ‘The you rolling your eyes meme’… she knows it from memes”.

“The Office” is now the perfect example of how YouTube’s and TikTok’s algorithms kill the value of content produced for old the industrialized model, and instead rewards format-agnostic relevance. The stories are proof of Rothenberg’s point that people consume content far more ecumenically - meaning, in diverse formats beyond traditional production - than via the industrial distribution mechanism of linear cable.

As I wrote in August, “an entire new generation of viewers consume “The Office” by the algorithm, and clips and memes generate more word of mouth and engagement for the show outside of Peacock than the full episodes or the “super fan” episodes of The Office on Peacock.”

What about advertisers?

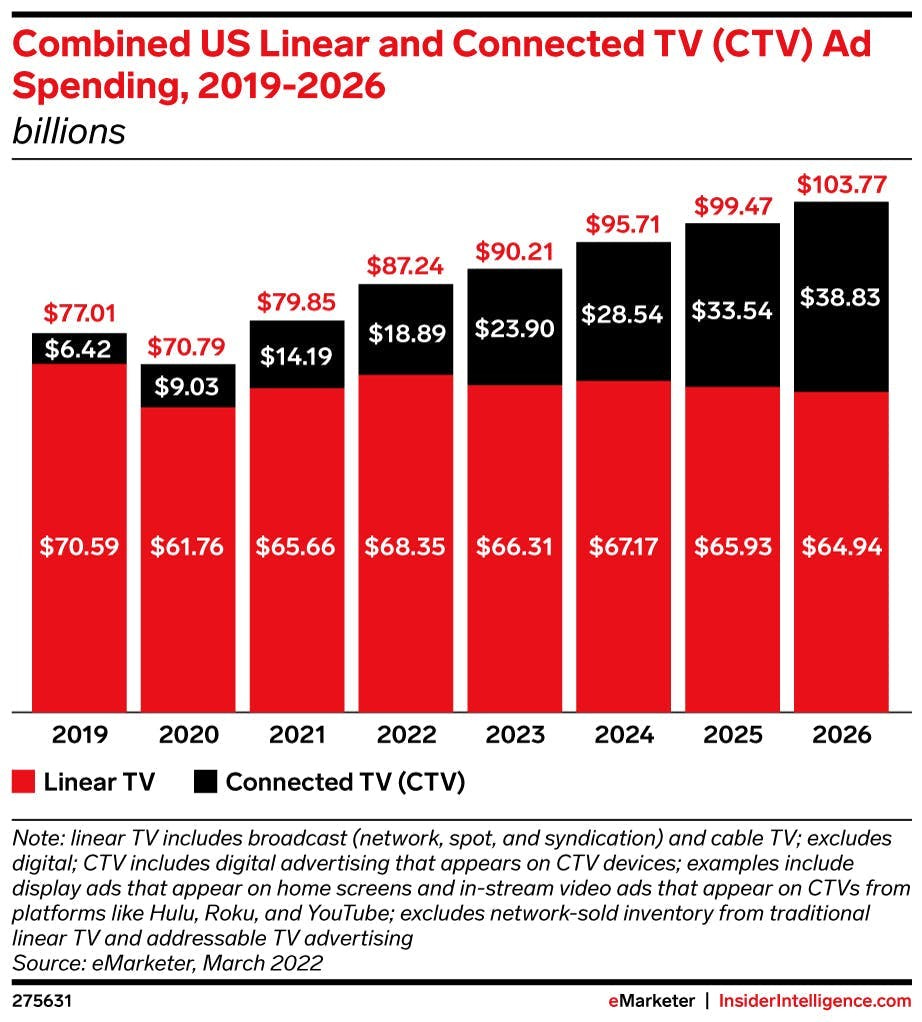

Emerging trends in advertising spend reinforce this point. They have historically spent between $60B and $70B per year in the linear TV ad market over the past few years. Now, with CTV, they are beginning to shift spend, as a recent eMarketer graph highlights.

I wrote about this graph being an “elegant misrepresentation” last month: linear TV spend also includes spend allocated to digital video and CTV. But, if the new standard for premium content is content that has made its way to be presented to an audience, then this chart also does not tell the complete story of advertising. Because, if advertisers value high production less, and relevance to users more, then they’d placing bets that reflect that business logic more.

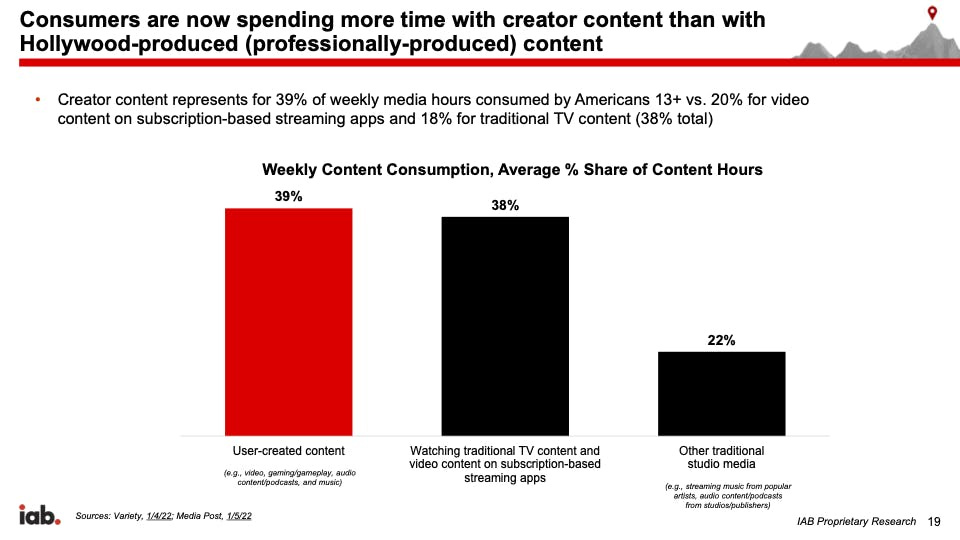

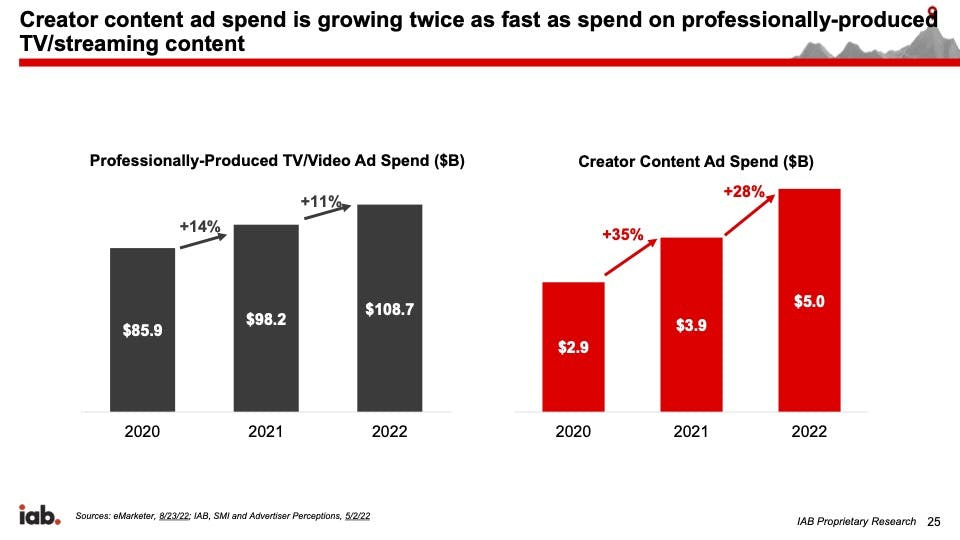

A slide in a presentation at the IAB Brand Disruption Summit 2022 by Chris Bruderle, IAB’s Vice President of Research & Insights, suggested this trend is true.

First, consumers are now spending more time with faster, cheaper and sometimes better creator content than more expensive professionally-produced content. And, second, advertisers are quickly shifting budget to user-created content.

We also know from YouTube that it had “strong growth in Upfront commitments” and one senior YouTube executive recently shared with me that he believed they took market share from linear at 2022’s upfronts.

The obvious story is about the emergence of the creator economy. YouTube has paid out $50B to over 2MM creators over the past three years, and therefore creator content is increasingly important to the relevance of suggestions YouTube’s algorithm makes on CTV screens. But, if we assume that premium content is content that has made its way to be presented to an audience, then 2MM YouTube creators more driving relevance for "ecumenical" consumers on YouTube's home screen and that is what makes their content premium.

That's not a story about the creator economy or the attention economy. It's something much closer to Rothenberg's point: creators are simply capitalizing on the de-industrialization of production and distribution models. The better they serve those trends and consumer interests.

So advertisers value legacy production value less and less because they perceive it to be less relevant to consumer interests. They may spend $68B on linear now because linear charges a premium, and perhaps they still see it as premium content, but it's not actually premium content.