In Q1 2023, PARQOR will be focusing on four trends. This essay focuses on "Media companies have millions of consumer credit cards on file. What happens next?”

The PARQOR Private Slack now live!

We are starting simple and small. If you are on the free tier and are interested in testing it with me, please respond to this email.

I argued on Monday that Disney CEO Robert Iger’s rethink of “general entertainment” effectively asks: “Why are we spending billions to compete with and lose share to free services with a similar value proposition?” I think Iger was framing Disney’s streaming value proposition as:

[Value Proposition of Content Library] = [Owned IP] + [Licensed IP]

In Iger’s framing, the value of Owned IP to a legacy media streaming business is greater than the value of Licensed IP. There are two problems with this framing.

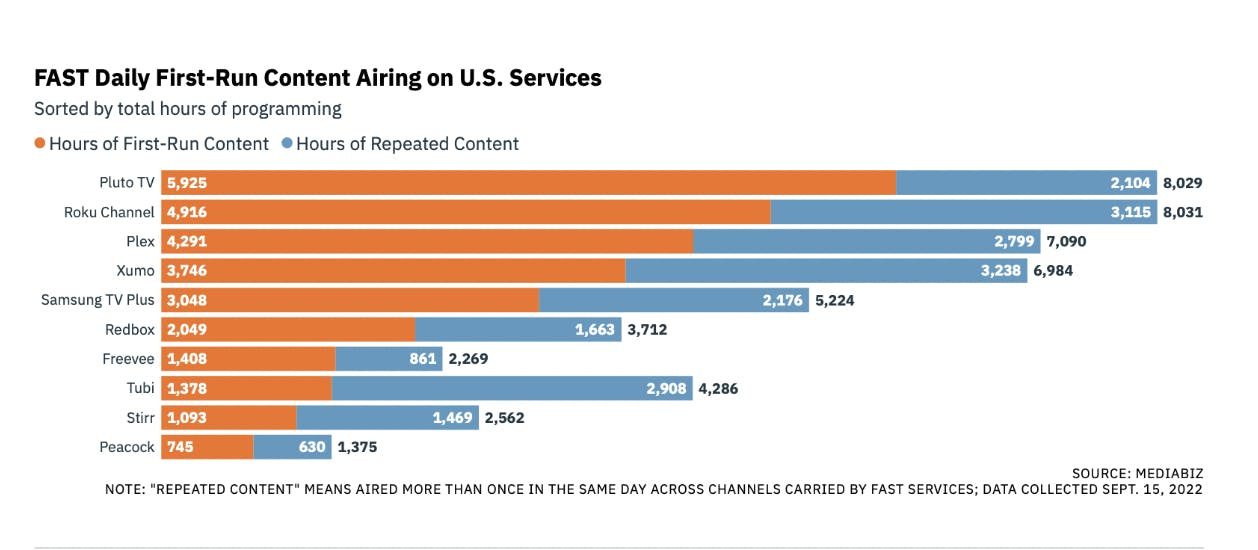

The obvious one is that Iger is complaining about the economics of distributing “undifferentiated” licensed IP. But the economics of licensing IP for *subscription streaming models* are inferior to the economics of licensing IP for *Free ad-supported TV services* (FASTs). For example, Pluto TV only pays a variable share of ad revenues for Licensed IP, whereas Disney+ licenses content with a fixed fee per play based on rate cards and a variety of other variables.

The less obvious problem is that the software-related variables of user experience (UX) and user interface (UI) should also be reflected in this “equation”. The UI consists of all visual elements of a streaming service (e.g., fonts, colors, layout) and the UX is the user-friendliness of using the service, and what the user sees and feels while using the application.

Key Takeaway

Disney’s streaming businesses are not only competing with other content libraries. They are also competing with the UIs and UXs of other software that leverages licensed IP more cost-effectively.

Total words: 1,900

Total time reading: 8 minutes

For example, Disney+ and Hulu share some commonalities in UX and UI for video-on-demand (VOD) streaming services: The tiles for content look similar in shape and size (UI), and the experience of browsing through them on the homepage is similar (UX). The UX for searching for content and exploring the libraries is quite different in each app (the distinctions are even clearer in the virtual MVPD Hulu + Live TV).

But licensed IP has a more nuanced business purpose within Hulu: to cost-effectively drive engagement within its UX and UI to marginally drive growth and engagement, and to reduce churn. Whereas the business purpose of licensed IP within Disney+ in Canada, Europe, MENA, South Africa, and parts of Asia-Pacific — where Star is included — is to offer “general entertainment” content for adult subscribers. The expectation is that more content will lead to more growth and lower churn, and Iger is openly conceding that has not been the case.

These two problems are flaws on their own, but together they reveal a deeper flaw in Iger’s framing. In streaming, the best business models for “general entertainment” understand their value proposition exists within the intertwining of three value propositions:

A library of Original IP

A library of Licensed IP,and

The service’s software or platform.

In other words, Disney’s streaming businesses are not only competing with other content libraries. They are also competing with the UIs and UXs of other software that leverage licensed IP more cost-effectively with consumers. The economics of Licensed IP within these different UIs and UXs helps to highlight this competitive dynamic.

UI/UX

Generally speaking, there are basically three UIs/UXs in the streaming marketplace:

The personalized UI/UX of Netflix and Hulu (and HBO Max, to an extent);

The non-personalized UI/UX that makes every subscription and free-ad-supported service look and feel the same (all services in some form or another); and,

The EPG (Electronic Programming Guide), which is Pluto TV’s default but is also a secondary option on Roku, Peacock, Tubi, Amazon’s FreeVee and other services.

Disney is unique because it owns both Hulu and BAMTech, which is the platform that powers Disney+, Star and Star+ and offers a non-personalized UI/UX. So, it owns and distributes two different UIs/UXs in the marketplace.

Licensed IP & personalized UI/UX

Licensed IP offers marginal value in a personalized UI/UX. Meaning, Licensed IP offers marginal or even fundamental value to audiences who may not be looking for Original IP. Having more titles in a library gives the personalization algorithm more “at bats” to engage the consumer and reduce their likelihood of churn. It also has the purpose of improving the service’s data on both the customer and broader demographic engagement with its library of content.

In a personalized UI/UX model, the economics of licensed IP are variable costs depending on how and when the licensed content is consumed. But, these costs may be justified if the data suggests they help to drive growth and/or reduce churn. For example, this rationale drove Netflix to spend $500MM in 2019 to distribute “Seinfeld”, which was one of the top 10 overall streaming programs in the U.S. in 2022 overall, according to Nielsen. Netflix’s churn spiked to over 3% in 2022 due to larger trends.

Its churn remains the lowest in the U.S. market in part due to content licensing bets like this: it had nine out of the top 15 acquired streaming programs in 2022, including “CocoMelon” and “Grey’s Anatomy” in the Top 5. Notably, only two Disney+ titles — Australian animated kids’ show "Bluey" and “The Simpsons” — made it into the Top 15. This suggests that Disney+ can drive viewership at scale, but it had no original series in Nielsen's Top 15, and its best performing content were movies (10 out of the Top 15 streaming movies).

Licensed IP & non-personalized UI/UX

As I argued on Monday, Iger’s complaint about “undifferentiated” content focused on the economics of licensing IP for a non-personalized UI/UX. He does not describe the problem in terms of UI and/or UX, and he is not alone among media executives in doing so. That may be because it may confuse investors, but Netflix management comfortably discusses its UI/UX on calls, so it would not be unusual.

All of his subscription-supported competitors (and not named Netflix) license movies and/or TV series as part of their respective value propositions to consumers, too. But none have not built differentiated UXs or UIs for their services, distinguishing from each other primarily in font and color choices. This is an outcome that suggests a collective risk aversion across the marketplace and is one outcome of the increasing commoditization of streaming technology.

The Licensed IP model for non-personalized UI/UX has two variations. There is the rate card model that all subscription streaming services use, as I described above. There is also the revenue share model of FASTs, which I also briefly described: only paying licensors a share of ad revenues monetized with the licensed content. The economics of the latter model involve no variable costs.

After spending billions of dollars over the past three years to invest in a large content library, Disney and others are now learning in real-time that Licensed IP has more value in a model like Hulu’s or Netflix’s, and almost zero in theirs. Disney lost $4B in 2022 in its DTC business, alone. Hulu generated $6.5B or one-third of $19.6B in DTC revenues, so there is evidence that Hulu is profitable and the other services — which have international distribution and therefore higher operating expenses — are not.

Paramount reported this morning that it lost $1.8B in streaming in 2022. It grew subscription revenue by 48% year-over-year, leading CEO Bob Bakish told investors this morning that "General entertainment clearly makes sense for us." It may be counter-evidence of my argument, or it may be proof of the success of hard-bundling — Paramount's strategy of partnering with local MVPDs internationally to bundle Paramount+. I believe it is the latter.

The EPG

I think Bakish's statement is more right about Pluto (78.5MM monthly active users and $1.1B in revenues, flat year-over-year) than it is about Paramount+. Pluto's primary interface is the EPG is a unique model for licensed IP and is worth discussing briefly. I wrote in October:

Pluto takes the familiar format of an electronic programming guide (EPG) – where content sits “cheek by jowl” and is filled with hundreds of individual channels of Paramount-owned content and third-party licensed content. It has long bucked the trend of streaming interfaces that either rely on personalized recommendations or do not and instead demands much more hunting and pecking from the user.

Another way of describing this advantage is something IAB Executive Chairman Randall Rothenberg made on Twitter back in April: “because [FASTs and niche services] are live, they don’t force the viewer to commit to a choice; she can go back to being a white-noise-consuming, channel-surfing couch potato.”

This point about “forcing the viewer to commit to a choice” is key. Streaming services and FASTs require choosing content to watch from the beginning. But an EPG like Pluto offers a long list of channels to watch, everything from curated channels around a genre (the Slow TV example I offered on Monday) to single-series channels and linear channels.

Variety recently interviewed an executive at Fremantle who estimated that to start a new FAST channel, one now needs 150-200 hours of content at the outset, with a content refresh rate of 10%-20% every month. The EPG, like its relative in linear distribution, is live and constantly evolving.

Its economics for Licensed IP are also better. Paramount streaming head Tom Ryan told Puck’s Matthew Belloni last October on The Town podcast: “If you can amortize the cost of content over a much larger group of users and hours than a smaller player can, and so when we go out and do an exclusive deal with a third party that’s not Paramount, we’re able to compete well we know we can get an ROI on that content better than some others can.”

As I argued then, Ryan is saying that Pluto’s large base and high engagement drive more and perhaps longer-term consumption of licensed content. He is implying that the EPG UI/UX helps to drive a better long-term consumption curve of content on Pluto than on other subscription, AVOD and FAST services.

In short, the EPG and the programming of first-run Licensed IP create a higher probability that licensed content will be consumed. There is no similar guarantee in streaming without a recommendation algorithm.

The best (?) model for licensing IP

The point here is not to flag (or flog) Bob Iger’s framing of “general entertainment” as mistaken or unusual. Rather, it is a valuable lens for highlighting important nuances of licensing models and UI and UX across the streaming marketplace.

To rephrase Iger’s rejection of personalization for Disney+ —“I think if people are clicking on Mickey Mouse, they mostly want Mickey Mouse” — Iger owns *a* solution to his problems with “general entertainment” in Hulu. It has a personalization algorithm, and I would argue it is the third best in the marketplace behind YouTube and Netflix. It has a sophisticated ad-targeting solution that advertisers trust, to boot. In short, Hulu has a UI/UX that offers personalized solutions/alternative content for subscribers when they do not want Mickey Mouse.

But a complex set of factors are obstacles to Hulu as a solution. Disney has been building its streaming services upon BAMTech since 2015, long before its 2019 acquisition of Hulu via its 21st Century Fox. Second, its contract terms with Comcast for acquiring Hulu in January 2024 is based on the greater of $27.5B or Hulu’s fair market value then. Both are costly counter incentives to Hulu ever becoming a default solution for Disney’s streaming business.

Iger could end up being out $9B or more when buying out Comcast in 2024, and that will be in addition to the $3B he invested in BAMTech. In other words, he will have spent $12B or more to have built his streaming future on a platform that works best for niche consumption of Disney brands and franchises.

There are no easy answers for Iger or any other CEO who have built upon a non-personalized UI/UX. I would argue that a key reason for that is that none are CEOs with a software or computer science background (I argued this last week). Meaning, the choice of Hulu versus BAMTech is not necessarily a binary choice (in practice it was not an easy one). Ultimately all their streaming futures hinge on their software or platforms.

It is a tension, one that perhaps a different CEO with a deeper background in software would understand how to navigate and determine a better software solution for licensed IP. Iger is not unusual — every other legacy media CEO faces the same question, with the twist that Iger is the only possessing the solutions. But it is increasingly clear that, if streaming is indeed the future of Disney’s business, his successor will need to be a different skillset to solve it.