Member Mailing: "Four Powerful Growth Vectors" for Modern Storytelling Companies, Which Ones Are Viable?

Key Takeaways

How will media companies find growth at a time when streaming growth seems harder to come by?

WarnerMedia CEO Jason Kilar recently suggested there are four vectors: streaming, FAST channels, gaming and digital collectibles

We can see which media companies are the best positioned modern storytelling companies in the 21st century with the PARQOR Hypothesis

But, to solve for gaming and collectibles, these companies may need to shift to a user-first, sandbox development model for storytelling with IP

If past is precedent, we may be a decade away from that shift, at least. Or, more likely, we may never see it.

Last Friday I had a brief exchange with WarnerMedia CEO Jason Kilar on Twitter after he responded to my opinion piece on The Information - "A Vibe Shift Is Brewing in Streaming":

Andrew, I believe there are 4 powerful growth vectors - in terms of audience, revenues, and cash flow - for the best positioned modern storytelling companies: streaming (but only for those that can achieve scale…many won’t), FAST channels, gaming and digital collectibles.

I asked him about collectibles - because the other three vectors made sense and I am skeptical but fascinated about collectibles. Jason responded:

Beloved characters and worlds matter. So too does community. I believe those that have the ability to seamlessly deliver both (which requires storytelling chops, community-building/nurturing chops and tech/product/design chops) have a big opportunity in digital collectibles.

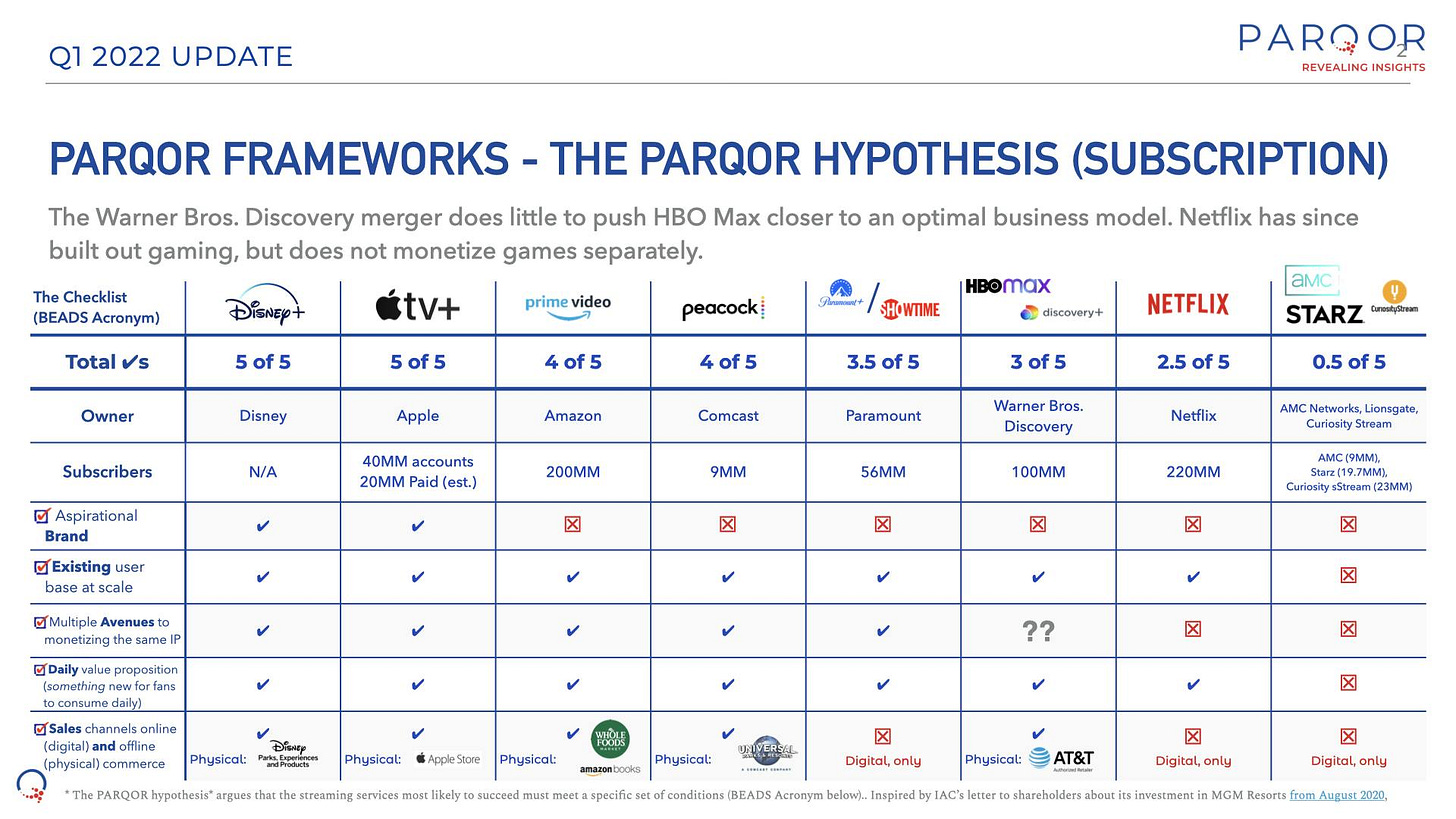

To date, I have been analyzing media businesses with the PARQOR Hypothesis, which is basically a framework to help understand the advantages and disadvantages of legacy media streaming services relative to pure-play streaming companies like Netflix. [1]

The PARQOR Hypothesis analyzes modern storytelling companies with a streaming service in the 21st century. These companies must have five attributes, and Disney is the paradigm (BEADS acronym):

✅ an Aspirational Brand (Note: IAC uses other adjectives like "preeminent" and "iconic", too)

✅ Existing user base at scale

✅ Multiple Avenues to monetizing the same IP

✅ Daily value proposition (something new for fans to consume daily), and

✅ Sales channels: Online (digital) and offline (physical) commerce (e.g., merchandise)

Kilar's tweets do not map neatly to the PARQOR Hypothesis. For instance, digital collectibles fall under any and all of Multiple Avenues to monetizing the same IP, Daily value proposition and online Sales channels.

Nor is it a set of attributes a single company "must" have. For example, Disney inspired the PARQOR Hypothesis (albeit indirectly, via an August 2020 IAC letter to shareholders about MGM Resorts), and it does not meet all four conditions:

❌ Free, Ad-Supported TV, or FAST (Hulu and ad-supported Disney+ are not free)

✅ Streaming at scale (196MM subscribers across Disney+/Star, Star+, Hulu, ESPN+)

⁇ Gaming (ambiguous because Disney licenses games out to third party developers)

✅ Digital collectibles (Golden Moments Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs))

But, Disney is well-positioned as one of the top two streaming services globally. So, Kilar is implying streaming will be a growth model for Disney, and Gaming and Digital Collectibles could become growth models, too.

Both perspectives offer two different lenses on the same problem: how will media companies find growth at a time when streaming growth seems harder to come by?

The PARQOR Hypothesis helps to answer this question from one angle: "Which modern storytelling companies in streaming are the best positioned for the 21st century?"

And, Jason Kilar's perspective helps to answer the question from a different angle: "Which ones have powerful growth vectors in place?"

There is also a third angle worth touching on given that I recently wrote about it in Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC), Hello Sunshine, World of Women & New Frontiers for IP: "Given what we know about BAYC, so far, are digital collectibles a viable growth model for modern storytelling companies in streaming?"

A recent interview with BAYC creator Jenkins the Valet helps to answer that question, and highlights the particular challenges for legacy media companies in the digital collectibles space.

Best Positioned Modern Storytelling Companies

Recently I have been asked how and why I use the PARQOR Hypothesis framework. The simplest answer is, it is a checklist of what assets a modern media company has, which ones it lacks, and how its checklist of attributes compares to the competition.

So, in comparing Disney to a pure-play streaming company like Netflix we see that Disney has operational and revenue model advantages over Netflix. Notably, Disney has Multiple paths to monetizing its IP - including Theme Parks, which is up to 40% of its Operating Income - while Netflix continues to iterate (and fail) towards that model, relying 100% on its subscription revenues for Operating Income.

It also offers a window into why the Warner Bros. Discovery merger may help solve for streaming, but why the merged entity will still have limited paths to monetizing its IP. WarnerMedia licenses its IP to both Universal and Six Flags Theme Parks, and 10% of WarnerMedia's operating revenues and less than 2% in Warner Bros. Discovery will come from gaming.

Which PARQOR Hypothesis companies have any or all of the powerful growth vectors Jason Kilar outlined?

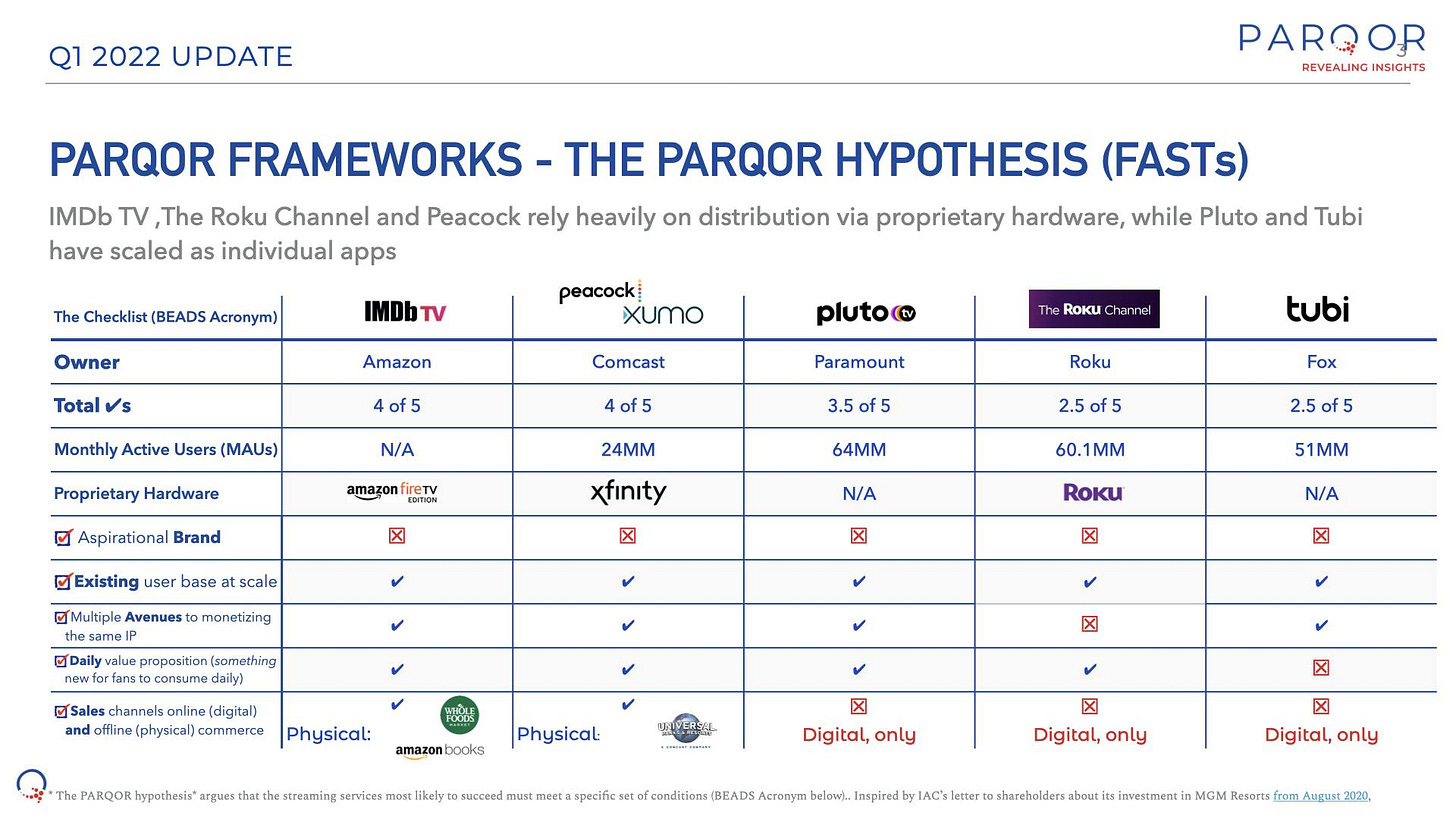

FASTs

It is interesting that Kilar highlights FASTs as a competitive advantage.

First, they have distinctively different business objectives across the streaming marketplace:

For Paramount (Pluto) and Fox (Tubi), they drive marginal ad revenue growth for the larger business, but have exponential growth rates on their own: Pluto drove over $1B in revenue in 2021, up from $210MM in 2019 Tubi projected to reach $700MM in 2022, up from $145MM in 2020;

For Roku, The Roku Channel FAST is fundamental to its business model as it drives greater margins than its hardware business (100% of operating income in Q4 2021), and it has recently been investing more in original content to drive this model; and,

For Amazon, IMDb TV seems to be an increasingly larger part of the puzzle for its Amazon Advertising $31B growth story (especially after the MGM acquisition).

Peacock seems more fundamental to Comcast's ambitions for evolving NBCU's model past theatrical and linear TV in the streaming era, both within and beyond its Xfinity ecosystem. But, the service seems to be suffering from both poor execution to date (it generated $778MM in 2021 and lost $1.7B), and having defined its target customers too broadly at launch.

As for Xumo, it seems to be a better business for Comcast as SaaS, powering streaming TV channels built into LG's smart TV operating system webOS. It is also preloaded on Comcast platforms — like its Xfinity X1 set-top box, Flex streaming box, and new X-Class smart-TV line. So it generates marginal ad revenues, too. It seems to be a valuable line item that performs well enough but does not (yet) merit the spotlight.

FASTs offer real growth opportunities, generally, but their business objectives are fundamentally different for each company that owns one.

Streaming at Scale

Kilar's implicit point is there are only really three streamers at competitive scale: Netflix, Disney, and HBO Max with discovery+. Maybe there will be a fourth and a fifth - Amazon Prime reaches 200MM subscribers and Paramount seems well-positioned to reach 100MM subscribers by 2024. But even then, it may be at fraction of the scale of the top 3.

Effectively, there are limited opportunities for growth in this growth vector. I like the imagination of Starz CEO Jeffrey Hirsch on this point:

And so to me, mass consolidation is coming, whether it’s commercial consolidation on deals and bundles or full consolidation with M&A. It’s local over-the-air broadcasters in France consolidating with global players. As you get out in the next four to six years, people are really going to start to pull the best from each territory around the world and consolidate into these four to six global players that own the streaming businesses.

This reads like a reasonable prediction of how growth will actually manifest in streaming. But, as Kilar warns, some services still may not scale enough to survive.

Gaming

Five companies with streaming services have their feet in gaming: Amazon, Apple TV+, Disney, Netflix and WarnerMedia. But, they each approach it in different ways:

Amazon has Prime Gaming, which offers in-game content for users favorite games, free games to download, and a free monthly channel subscription on Twitch.

Apple has Apple Arcade, a game subscription service that offers a library of games to subscribers, and seems tied to Apple TV+ only in Apple One bundle deals.

Disney has "given up on video games", licensing it out to third-party video game developers since 2016.

Netflix has mobile gaming, which is beginning to build out and tie to existing Netflix IP (it is releasing three new games this month).

WarnerMedia has a quiet $1.8B annual business, and as Kilar told Peter Kafka on the Recode podcast, "we’re actually building our own immersive persistent environments where our beloved characters are in Warner Brothers games as opposed to being present in other peoples games"

It is worth noting that it is up for debate whether Amazon or Apple have yet to truly establish themselves as "modern storytelling companies" with Prime Video and Apple TV+, respectively. Amazon has had a few hits in the space (The Boys notably being one, and a soon-to-be-released Lord of the Rings prequel). So, there is no real clear path to growth for these "modern storytelling companies" in both gaming and streaming.

I also think Kilar's "modern storytelling companies" term also implies Epic Games (Fortnite), Bungie (Destiny 2) or Microsoft (Minecraft). Each has pushed storytelling in gaming in new directions:

Fortnite focuses on "environmental storytelling": the island at the center of the game "is a place where players come together to hang out and shoot at each other, but it’s also a virtual world brimming with its own strange history" and where big events leave permanent changes on the island. (350MM registered players)

Minecraft takes a sandbox approach to storytelling: its chief storyteller Lydia Winters sees her role as "to create and curate a world players want to create in" and "enabling of all kinds of storytelling". (141MM users worldwide)

Bungie's Destiny 2 is an online-only multiplayer first-person shooter video game that has taken seven years to solve for a type of storytelling that is "only possible as a live-service game or MMO, where the game world changes and evolves over time, and the story evolves along with it." (~40MM players or subscribers)

The big challenge for legacy media companies is whether they can move into similar modern storytelling business models themselves. Kilar explained to Peter Kafka on the Recode podcast why legacy media companies have been hesitant to do so:

...if you have the capabilities and if you have the skillset in terms of leadership and talent to be able to lean into telling those stories, both in a linear fashion with narrative storytelling but also an interactive fashion with gaming. And so we happen to have that conviction, we happen to have that skillset - both at the leadership level and at the software developer level. So we're able to do it and we're able to do it with confidence and high judgment. Very few companies on the planet or in that position because gaming is hard to my earlier point and it’s not for the faint of heart.

This explanation is notable for two reasons. First, the successful growth models of "storytelling" in gaming are long-term, trial-and-error businesses where creativity takes a back-seat to the user. Developers launch, fail, learn, iterate and then repeat the cycle again over years. The examples, above, are three success stories, but there are many other imitators who have failed. Legacy media - obsessed with hitting quarterly numbers for investors - seems to avoid these risks of failure like the plague because it is, as Kilar says, "very hard" to execute successfully.

Second, WarnerMedia seems less risk-averse than other legacy media businesses with streaming services. That has been true both in streaming - where it has gone all-in on direct-to-consumer business models (including recently ending a distribution agreement with Amazon Prime Video Channels, and nominally losing 5MM subscribers in having done so) while others (Paramount) are moving away from the model - and in gaming. [2]

More broadly, one gets the sense that growth from gaming is unlikely to happen within a legacy media company, and is more likely at modern storytelling companies outside of legacy media.

Digital Collectibles: Where Do Web3 & Legacy Media Overlap?

It is worth diving into digital collectibles, separately, because as I wrote above they do not fall neatly into the PARQOR Hypothesis. Kilar suggested we should pay more attention to the market opportunity because:

Physical collectibles by some est are a $500B industry. The “job they do” for people = expressing oneself, feeling part of a community (belonging), providing social connection, serving ego, and economic upside in some cases. I believe digital collectibles can do those jobs better

He suggested two value propositions for consumers in digital collectibles:

Beloved characters and worlds

Community

To deliver both requires three sets of "chops" or know-how at a modern storytelling company:

Storytelling

Community-building/nurturing chops, and

Tech/product/design chops

There are few companies scored by the PARQOR Hypothesis that have all three "chops". Disney, NBCUniversal and WarnerMedia are the obvious choices with their TV and movie production studios. Paramount has historically had a reputation for world and character-building, but is in the early days of a pandemic-delayed comeback story.

But the optimal model Jason Kilar points to here is the NFT collective Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC), which I have written about recently:

Yuga Labs Acquires CryptoPunks & Meebits IP from Larva Labs (March)

Bored Ape Yacht Club, Hello Sunshine, World of Women & New Frontiers for IP (February)

Where Web3 & Legacy Media Overlap (January)

[AUTHOR'S NOTE: a reminder, if you would like to read any of the paywalled archives, please respond to this email and I will send them to you].

As I wrote in February, BAYC is a particularly interesting case study of whether NFTs mark "the birth of a new media model". However, Yuga Labs wrote in a recent Mirror post that it does not see BAYC as a "one-size-fits-all model".

So why would Kilar be bullish because of BAYC? The backstory of Jenkins the Valet is valuable to answering this question.

BAYC's Jenkins

Web3 Breakdowns host and BAYC Member Eric Golden - a former portfoliio manager at Fidelity who is now one of Web3's loudest proponents - recently interviewed the creator of Jenkins the Valet, a fellow BAYC member and "one of the first creators to explore the full potential of utilizing the IP granted and ownership of an NFT".

Jenkins, a creative writer himself, explained the backstory he imagined for his Bored Ape Jenkins:

The story is that Jenkins is not a member of the club. He's from the other side of the swamp. And he was so lucky and fortunate to get his job as head valet. I mean to the point where his mom cried. And since getting the job as head valet at the Yacht Club, he's practiced discretion because he's rubbed shoulders with some of the most powerful and influential apes and he's done all of their odd jobs. He's snuck mistress into the club through laundry carts. He's held private keys for people. He's sold private keys. I mean, there's nothing that Jenkins hasn't done.

The entire interview is worth listening to, but this particular section highlights what Kilar was getting at:

In 2020, folks listening will recognize this if they spend time online, you started to see CryptoPunks being used as people's profile pictures... It was a symbol, something that you believed in or that you were willing to put your money in this new product or something like that. But what people weren't doing was creating characters out of those avatars, especially when Bored Apes came to market in late April and you started to see apes on the timeline, they did two incredible things. The art is unbelievable and every single ape looks like it has a story to tell. They're so distinct. You recognize them on the timeline. And the second thing that they did was that they gave commercial rights to the holders.

And I'm not sure that anybody was really imagining building big businesses out of them, but by even giving the commercial rights to the holder, I think what they were saying was, "This is yours. You do what you want with it. It can truly be like a layer of your identity in the sense that we don't own it at all."... [My co-founder] and I realized that apes and eventually other NFT avatars could be the next generation of household characters. They look like they have these rich backstory, but then no one was telling them, because people were using the avatars for their own profile pictures.

This story embodies Kilar's point: "Beloved characters and worlds matter. So too does community."

The challenge is Jenkins' story seems like an unusual, if not hard-to-replicate, confluence of events that legacy media executives (in book publishing) rejected:

I mentioned it was August 4th, 2021 when we did our primary sale of Writer's Room NFTs. We had known for a long time that really no matter what happened with that sale, we wanted a really proven writer to write our first book. And it's one of the things that we think is a major benefit to our business is that, you've got this really authentic Web3 community. And if you pair that community with elite creators, then you can tell a better story than anybody could do on their own. And so that was very much part of our thesis, even back then. And so right after that sale, and even a bit beforehand, we had been reaching out to literary agents and authors, because we were like, "We don't know any better."... And 90% didn't respond and the other 10% were just straight up mean.

This story reflects why the Jenkins interview is so valuable: it highlights both unusual circumstances of success in digital collectibles, and the obstacles presented by incumbents, whether because of risk aversion and/or lack of education on the Web3 business model.

Kilar's point is that Jenkins and other BAYC collectibles are emerging market precedent that offer guideposts for stronger relationships between fans and their favorite characters - and for media companies with fan communities - while also driving growth at media companies that need that growth.

Is Jenkins the future of modern storytelling companies?

Can PARQOR Hypothesis companies - which were all slow to adapt to streaming except for Amazon - now solve for growth with BAYC-like digital collectibles? Especially if they have storytelling chops, community-building/nurturing chops and tech/product/design chops?

The short answer is no. If there is anything that this interview with Jenkins highlights, it is how two entrepreneurs took enormous risks that most risk-averse legacy media executives would not take.

Also, as I highlighted in Where Web3 & Legacy Media Overlap, the BAYC model relies on Exclusive membership - and not Existing User base at scale - while holding all other four attributes of the PARQOR Hypothesis static. Modern storytelling companies pursuing the Web3 model may require much less scale to succeed than legacy media companies. Yuga Labs is projecting net revenue of $455MM in 2022, or 70% of Peacock's 2021 revenue, alone.

That said, it is early, and it is worth reading/listening to the Jenkins interview to get a sense of which moving pieces map to existing media business models. As I wrote above, digital collectibles fall under any and all of Multiple Avenues to monetizing the same IP, Daily value proposition and online Sales channels in the PARQOR Hypothesis.

If a company can solve for digital collectibles, they fit naturally into an optimal media business model in the 21st century.

Conclusion

The PARQOR Hypothesis helps to highlight how limited the options for growth are for legacy media companies with a streaming service, especially.

It also highlights how the customer relationship between most legacy-media-companies-in-streaming-not-named-Disney and their audiences is not seamless. [3] That, even if there are multiple Avenues to monetizing IP across other channels, or online sales channels that could be built, those business models are not always feasible within those ecosystems. And, because those business models are not always feasible, solutions for growth like the ones Jason Kilar laid out are not always available.

Could a Disney solve for digital collectibles? Perhaps. It has the community and it has the IP. But, it also has had greater success solving for gaming via third-parties than in-house, and it is currently navigating some difficult operational questions around how it will continue to grow Disney+.

As for WarnerMedia, even if it successfully pulls off a digital collectible business model around its Harry Potter, DC Comics or Looney Tunes IP , both Universal Theme Parks (Harry Potter) and Six Flags Theme (DC Comics, Looney Tunes) still own a more direct relationship between WarnerMedia's IP and millions of its target customers who visit those theme parks. Digital collectibles seem to a smaller Total Addressable Market, even if valuable to maintaining relationships between fans and their beloved characters and the broader fan communities.

Last, the Jenkins story highlights two important details that legacy media companies will have to solve for:

Exclusivity matters more than scale in digital collectibles (NFTs are issues in the hundreds or thousands), and

Executives will need to be willing to fail 90-100% of the time in order to find success.

The digital collectibles model makes a small number of super fans who are willing to spend hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars very happy. That is a business model, but it is not one at scale.

Perhaps WarnerMedia and Disney can unlock the enormous value in digital collectibles that BAYC has figured out. But, for these companies to solve for gaming and digital collectibles is going to require fundamental shifts in management and operational culture to become more conducive to game development and Web3-oriented DTC business models.

If past is precedent, we may be a decade away from these shifts, at least. Or, we may never see it because as Kilar said about gaming, it's "hard... and it’s not for the faint of heart".

Footnotes

[1] Kilar's "modern storytelling companies" term seems more accurate than "legacy media companies" here because it better describes what Apple, Amazon, Comcast (owner of NBCU and Peacock) and Roku are attempting with original content in streaming.

[2] Jason Kilar's track record at WarnerMedia to date (2021's day-and-date "Project Popcorn" release strategy, especially), and his interview with Peter Kafka both reflect how he and is team are not as risk-averse as other legacy media executives. So his perspective has limits in its applicability to other C-suite executives at other PARQOR Hypothesis companies. Whether WarnerMedia it will find growth in gaming remains to be seen, especially with new Warner Bros. Discovery leadership who will be more focused on extracting growth from streaming and linear.

[3] It's worth noting something CNBC's Alex Sherman wrote on Disney CEO Bob Chapek's ambitions to improve the seamlessness of the Disney consumer experience:

Ideally, Chapek would like consumers to experience a more unified digital Disney experience, whether it’s logging into Disney+ or buying merchandise from the online Disney store or managing theme park experiences with Disney’s Genie service, which is a kind of digital concierge. Internally, some employees informally speak of this grand challenge of unifying Disney technology and experiences as “One Disney.”