Member Mailing: If Streaming Growth *Is* Slowing, What Will Advertisers Buy In CTV?

Key Takeaways

The Connected TV ad marketplace has transformed from a growth story into a story about growing risk for all participants

AVODs and FASTs need higher CPMs from CTV and are betting on them for revenue growth

One implication is ad buyers seem not to currently value CTV inventory at the prices ad sellers offer.

Reach is a challenge: the average campaign in a recent study reached only 13% of the available U.S. CTV households

Advertiser demand for CTV inventory may be more selective than the data suggests.

Journalist Mike Shields recently wrote about an emerging "credibility problem" in the Connected TV (CTV) marketplace:

Right now, the CTV market is on fire, so it’s not so tragic that Nielsen has struggled to keep up and roughly 15 would-be replacements are vying to squeeze in. But you can envision what happens over time when there is no third party source of truth - particularly in a medium that already seems highly susceptible to fraud.

I’m not saying that some of the numbers being thrown around in CTV smell fishy, but they don’t smell great, particularly if you go out in the world and talk to people.

Shields concedes that he "mostly believes that these public companies wouldn’t mess around with these kind of numbers". But, from his experience, "this self reporting is not a good look."

This challenge of self-reporting reflects the flip side of the issues I covered in last week's Does $115B+ in Content Spend Reflect Inelastic Demand? Or Marketing Challenges in Streaming, Instead?

Meaning, even if a streaming service can solve for marketing and audience demand for streaming is inelastic, will AVODs be able to drive their CPMs higher with CTV inventory?

Because that is the bet being sold by the likes of Hulu (which set the market precedent), Peacock, discovery+, and HBO Max with Ads. Growing content spend requires recoupment from growing revenues and larger audiences.

AVOD is an increasingly important part of that bet because it delivers marginal revenues to subscription, and it can attract audiences at scale at a lower price point. FASTs are investing in original content, too.

The best outcome is that inelastic demand and marketing drives more audiences and therefore higher CPMs given the higher market value of CTV inventory. But, given the recent challenges of both Netflix and other streaming services to solve for growth through marketing, that outcome seems unlikely in 2022.

Instead, if demand is elastic and marketing fails to drive more audiences, demand for all streaming - SVODs, AVODs and FASTs - will go down and CPMs will stay flat or go down. Throw in Mike Shields' point above that the CTV numbers "don't smell great", and the entire streaming ecosystem may be more fragile than we have been led to assume.

In other words, if advertisers cannot reach streaming audiences at scale and/or are unwilling to spend more for additional reach in AVOD and FAST, then all three models (SVODs, AVODs and FASTs) are primed to hit a wall in 2022.

[Author's Note: The rest of this essay will be exclusive to members, only.]

If you are considering becoming a member, are some recent mailings exclusive to members on this topic of AVODs and Connected TV from the Substack archive:

Amazon, NBCU, The NFL, & Addressable Advertising (March 2021)

An Evolving Tension Between Data and Context in AVOD (April 2021)

Who *is* the target customer for AVOD? (April 2021)

HBO Max's AVOD, DotDash, and Unlocking Value Through Fewer Ads (May 2021)

AVOD after the 2021 Upfronts (July 2021)

After Snap, Facebook & YouTube's Q3 Results, What Will Happen to Legacy Media AVODs? (October 2021)

What YouTube's Transparency Reveals for 2022 & Beyond (December 2021)

The Hulu Precedent

Legacy media bets on the AVOD model have followed Hulu's model of total ARPU of subscription revenues across two plans (with ads and ad-free) plus marginal revenues from advertising. So, Hulu is a helpful precedent here.

I wrote about the math of this model last May in HBO Max's AVOD, DotDash, and Unlocking Value Through Fewer Ads:

Hulu reported an ARPU of $13.51 in fiscal Q1 2021 across 35.4MM subs, despite having a high ad load per hour (nine minutes or less of commercials per hour, above). Assuming two-thirds of its audience chose the ad-supported $5.99 per month offering, which they did in fiscal Q1 2020, it implies Hulu generated $14.26 ARPU off its AVOD tier in Q1 2021, alone.

Hulu reported an ARPU of $12.75 in FY Q1 2022 on a higher monthly price of $6.99 for its ad-supported offering. Assuming two-thirds of its audience chose the ad-supported model, again, Hulu generated $15.58 off of its ad-supported offering, or $8.59 in ad revenue per user over the quarter (up from $8.27 or 4% from Q1 2021). [1]

That type of revenue would put the ARPU of HBO Max AVOD at $18.58, or~2x its current price, 55% higher than its ad-free tier, and 20% higher than Netflix's ARPU at its standard tier.

Core assumptions of Hulu's model are that a combination of growing CTV consumption, growing demand for CTV inventory, improving ad targeting, and increasing CTV consumption can drive CPMs higher, and therefore ARPU on AVOD higher.

It captures significantly more value on that bet with its virtual MVPD ($84.89 ARPU in FY Q1 2022) though at a fraction of the scale (4MM subscribers).

The FAST Marketplace in the U.S.

In the broader Free Ad-Supported (FAST) TV marketplace (Roku, Amazon's IMDb TV, Fox's Tubi, ViacomCBS's Pluto TV and, of course, YouTube), the model is advertising, only.

That inventory generally relies on a mix of owned originals, licensed content, and in the case of Roku and Amazon, some percentage of inventory on third-party applications (typically ~20% to 30%). Roku's and Amazon's model relies more heavily on CTV given the scale of their device penetration in the U.S., and also because both generate revenues taking a percentage of sales from AVOD and SVOD apps, but neither discloses those numbers.

One analyst recently argued "a material part of the company's growth has come from third party SVOD-related revenue contributions, which are set to slow."

They offer both CTV hardware and market-leading, advanced OTT and CTV advertising solutions. Roku (~51% of CTV users, according to eMarketer) and Amazon (45%) share the lead in the CTV marketplace in the U.S. (though Amazon has more devices worldwide (150MM) than Roku devices (56.4MM)).

Google does, too, with YouTube and its Android TV and Google TV operating systems, but it has a smaller share of the Smart TV marketplace in the U.S. (though growing). I wrote recently in A Big PR Push from YouTube & Hollywood-Meets-Creator-Economy why YouTube's strengths in Connected TV and the creator economy are so important:

[YouTube] is telling creators that it has advertisers and multiple paths to monetization, and telling advertisers that it has creators. Throw in its 120MM monthly Connected TV viewers, watch time on TV screens of YouTube content greater than 30 minutes has increased more than 90% in a 12-month period in the US, and YouTube is unusually positioned to capture the shift of $68B away from linear TV into digital.

Pluto and Tubi offer sophisticated ad targeting solutions, but they are not as advanced as those offered by Amazon, Google or Roku, and therefore may not deliver similar reach.

Three Problems Emerge

If Mike Shields' point that CTV numbers "don't smell great" is true, that implies three problems for the AVOD and the FAST marketplaces in the U.S.:

Neither may have sufficient scale or reach to capture much-need advertiser dollars,

Legacy media relies on both first-party and third-party channels (Roku, Amazon, Google) for ad revenues, and

In both cases, ad buyers may not always value CTV inventory at the prices ad sellers offer.

1. Insufficient Scale = Insufficient Reach?

Shields' point, above, questions whether scale exists in both FAST and AVOD, and both business models need scale. It seems counterintuitive to state this given the enormous scale of Roku and Amazon in the U.S., and the emergence of Smart TVs as a default consumer choice.

There is scale in the Connected TV marketplace, according to a 2021 study from Association of National Advertisers (ANA) and Innovid: approximately 75 million unique, addressable CTV households in the U.S. (out of an approximate total of 128 million).

But the same study says there is not reach: the average campaign in the study reached only 13% of the available U.S. CTV households. This implies that CTV ad technology may not be able to reach target consumers cost-effectively, and the ANA and Innovid study said exactly this: it recommended that upwards of 100 million impressions should be purchased to reach 40% of the U.S. CTV homes.

In other words, ad buys need to grow by over 300%, on average, for CTV to compete with linear. Ad spend on CTV is currently inefficient.

This data echoes something else Shields reported last October:

Is there enough CTV ad space out there?

“There is demand,” said Amy McGovern, vp of addressable sales, Warner Media. “One of the biggest challenges is scale.”

Second, it implies that the ad technology can deliver reach to CTV audiences at scale, but it is not a solution that matches ad buyer objectives or budgets (NOTE: more on this below under 3. Codependent Marketplace).

Putting the two and two together of Shields' reporting, advertiser demand for CTV inventory from AVODs with scale may not be as strong as the data suggests.

2. The Impact on First-Party & Third-Party Channels

The Innovid report also highlights the eCPMs for CTV:

The average eCPM of the campaigns in our study was $23, which sits in between the average CPM for U.S. primetime TV ads for broadcast and cable ($36 and $19, respectively). The average cost per unique reach for CTV was $123.

The good news is, that is the type of CPM that legacy media AVODs and FASTs seek in CTV. The bad news is they all may not be in position to capture it .

Meaning the least risky bet for advertisers is to spend on the platforms that have the most scale and with the technology to deliver the most reach: YouTube (120MM CTV viewers), Amazon and Roku. That outcome puts a legacy media app like HBO Max with Ads, discovery+, or Peacock in a difficult position with advertisers.

Advertisers needing reach will always find more reach from YouTube, Amazon or Roku than on HBO Max with Ads, discovery+, or Peacock.

It also means, given that these are platforms, advertisers may buy inventory on those apps as third-party inventory from either Roku or Amazon [2]. In doing so, they may get more reach than they would buying directly from HBO Max with Ads, discovery+, or Peacock because they would be buying across all inventory on Roku, and not just within a particular app (NOTE: I dove into this problem in Amazon, NBCU, The NFL, & Addressable Advertising last March). [3]

This points to a third problem: if that self-reported scale of platforms and services is all optics but not substance, then we are reaching a moment where the ad tech is hitting the limits of the reach it can deliver. Moreover, if Innovid's recommendation to ad buyers is to buy 3x the reach than they currently are, that will require ad buyers to spend more on flat or declining audiences.

That challenge is one that legacy media knows well in linear, where they have seen CPMs go up as linear audiences have declined but targeting has improved. It is an interesting question of whether this will play out in CTV and ad-supported streaming, too.

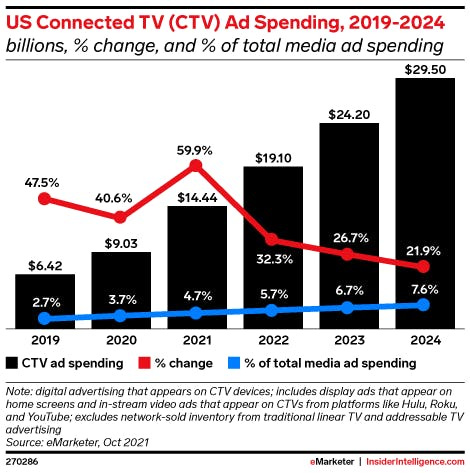

But targeting and measurement are still in their early days. As an investor in the CTV space the told Insider (subscription required), even if the ad spend is projected to grow by 50% by 2025:

"The ad spend isn't flowing as fast as people want it to because you can't measure it as well as you can the other stuff — the tech is still being developed".

3. Codependent Marketplace

I frequently re-use one of my favorite lines about the legacy media ad marketplace from Rob Norman (ex Group M) in this must-read opinion piece:

It would be ignorant to express relief that digital looks to be moving away from third-party cookies because, let's not forget, the tech giants are staying exactly where they are in terms of first-party data. That means premium publishers, and many advertisers who have a co-dependent relationship with premium publishers, need to focus on the intersection of context and data. They also need to think about what data matters most.

The implication of the quote for CTV is that ad buyers do not think much about context or data, and rely on relationships more for ad buying. That has not necessarily played out in CTV generally, but the Innovid data suggests that context and data are not valuable enough for ad buyers to spend more to improve the reach of their campaigns.

Instead, "codependent" relationships matter more than sell-side economics, and in turn can overwhelm the economics of emerging, smaller-scale line items like CTV or digital media revenues at legacy media companies.

Mike Shields had an example of this codependence in a previous post from a conversation with Vinny Rinaldi EVP of GroupM’s Wavemaker (reported by Mike Shields) last summer:

Rinaldi was talking about how CMOs and especially traditional TV buyers are obsessed with pricing when buying ad space - “chasing cost” particularly in the upfront. In so many words, Rinaldi was saying that old school TV buyers are so hung up on showing their clients that they negotiated a nice healthy CPM that they lean on buying cheap tonnage - which leads to the same group of heavy TV viewers seeing the same ad hundreds of times.

At the same time -and I’m doing a bit of interpreting here - those same TV buyers tend to balk at the high CPMs common to some ad-supported streaming services (How can I justify a $50 CPM on Peacock when I can get $3 on the ION network?!?!), despite the fact that increasingly CTV is the only way to reach certain people -and often these people are uber-engaged with their favorite shows. You can tell it frustrates executives accustomed to real-time bidding and the like.

This last point is key: CTV inventory is valuable, but ad buyers generally seem risk averse in buying it. They are unlikely to spend more on higher CPM inventory even when the reach is possible.

If self-reported reach is over-reported, that can only disincentivize the buying behaviors the CTV ad market needs to grow further. That puts the marginal higher CPMs that every service needs - but Peacock, discovery+, and HBO Max with Ads especially will need - out of reach.

Conclusion

There was one other signal from the marketplace last week, and it came from the surprise departure of Roku SVP and general manager of platform business Scott Rosenberg. It is not clear why he left, but there are questions hanging over its platforms business which post-Quibi acquisition is a mix of the ad business, marketing, promotion and partnership deals, and content acquisition.

Roku's platform relies on the fees from partnerships (meaning SVOD and AVOD services which distribute on the platform) and ad sales. The risk is whether those SVOD and AVOD services will struggle with marketing and churn over the next few years. I argued this will happen in last week's Does $115B+ in Content Spend Reflect Inelastic Demand? Or Marketing Challenges in Streaming, Instead?.

Assuming I am right, Roku will lose its first-party revenues (decline in ad inventory) and third-party revenues (fees paid to Roku as a percentage of total subscriptions). That may be why Rosenberg is leaving: he sees the writing on the wall that streaming CTV inventory may be too risky for risk averse advertiser demand.

Given Roku's growing bets on original content, it also leaves Roku in a similar position to legacy media AVODs: how will it recoup its content costs if it advertiser demand is risk averse and unlikely to pay premium CPMs or by the reach necessary for campaign success?

These risks seem to be greatest for emerging AVOD services banking on growing demand for CTV inventory: ad-supported models at lower price points may indeed attract more consumers at scale, but neither the scale nor the reach is going to be sufficient for risk-averse ad buyers comparing various alternatives.

The biggest risk for everyone is that CTV is very much still in an experimental phase, as I highlighted for readers two weeks ago in Is It Really a "New World" for Connected TV Ad Buyers?

It is far from a mature market despite its enormous scale, and counterintuitively it may not leave that phase anytime soon despite the scale of CTV adoption in the U.S.

Footnotes

[1] The math is: $12.75 = [.33*(6.99)] + [.67(x)]

$12.75 = $2.31 + .67x

$10.44=.67x

x= $15.58

[2] Or, a platform like The Trade Desk, which delivers programmatic advertising to digital video across OTT services. Connected TV is its fastest-growing channel and growing as a percentage of overall revenue.

[3] There would be other limiting factors on reach. Notably they would buying a fraction of available inventory for impressions served on a fraction of all devices. That scale gets further whittled down based on targeting goals.

However, they also would be buying reach across all Amazon or Roku FAST services and hardware.