In Q1 2023, PARQOR will be focusing on four trends. This essay focuses on "Media companies have millions of consumer credit cards on file. What happens next?"

Like millions of others (presumably), I watched the Chris Rock comedy special “Selective Outrage” on Netflix last Saturday. My initial reaction was that the viewing experience felt like “The purest uninformed viewing experience that Netflix has offered in the Internet era.”

There was also an intangible feeling that because I was watching this on Netflix I was sharing a moment with millions of viewers worldwide. It was similar to watching global sports events like the Super Bowl or the World Cup, but different in the sense that *everyone* was watching simultaneously *on Netflix*.

So, knowing the scale of Netflix made it all feel like a different collective viewing experience. I’ve watched live performances from the Coachella Valley Music Festival on YouTube before, and fans who tune in know when and where a concert is taking place. But YouTube never has promoted Coachella the way Netflix promoted “Selective Outrage” across the media and within its ecosystem of subscribers.

It certainly helped that it was glitch-free for me. Where Netflix goes from here is anyone’s guess. But the moment and the aftermath — Netflix’s first “water-cooler moment" for a live event — suggests that Netflix now offers the linear model’s value proposition to 230 million subscribers on a single platform globally. The linear and broadcast models now seem outdated. Nothing will be the same again.

A theme in 2023 has been growing uncertainty in the marketplace, and all signs suggest that Netflix’s success disrupted that uncertainty and created more. For this reason, I am going to do something slightly different this week. Rather than write an essay, I am going to lay out how I think the pieces are lining up for the rest of the year through the lens of each of PARQOR’s key trends.

Ideally, I am helping you think these changes through before you discuss them with your managers, clients and/or investors. The objective is to help you create greater certainty in a moment of growing uncertainty. This is the first of a series of four essays this month.

Key Takeaway

After Netflix’s big livestreaming accomplishment, everything in streaming and traditional media seems both possible and at risk of disappearing. The “pathetic dot” helps us to identify where certainty in the marketplace still exists.

Total words: 1,800

Total time reading: 7 minutes

A Framework Q1 2023, to date

Media companies with scaled streaming services now have an asset: millions of credit cards with recurring monthly revenues, impacted primarily by churn rate. But, as AMC Networks Executive Chairman recently wrote to shareholders, “the mechanisms for the monetization of content are in disarray.”

That statement means two things: first, as Dolan wrote, the “belief” was that cord cutting losses would be offset by gains in streaming. That has not happened.

Second, it implies that streaming is as much an insurance policy as it is a necessary evolution, so even if these databases of credit cards are valuable, management teams are not ready and/or able to go all-in on them as the future of their businesses.

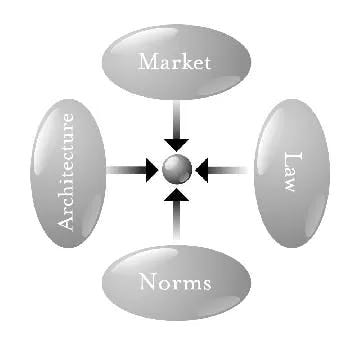

To help understand how this dynamic is playing out, we can use a diagram of a “pathetic dot” from Larry Lessig’s book, Code 2.0 (PDF available here, p.120).

Lessig writes: "In this drawing, each oval represents one kind of constraint operating on our pathetic dot in the center. Each constraint imposes a different kind of cost on the dot for engaging in the relevant behavior…"

I last used it in an essay last March. I believe it is a valuable checklist for thinking through the constraints around a problem in complex marketplaces like streaming. [NOTE: this analysis will not use the ethical lens, as it does not apply here.]

Marketplace lens

Many management teams are treating the financial and operational inefficiencies of the streaming business as a higher priority than revenue growth (which Warner Bros. Discovery’s recent earnings delivered, with flat growth and lower losses). This is partially because of the enormous long-term debt obligations they have, but moreso because Wall Street demands profitability over growth.

Almost all streaming services have seen growth plateau in the U.S. but continue overseas. Because international markets tend to have lower average revenue per user than the U.S. market, international growth only captures a fraction of the revenue of the U.S. market. So subscriber growth does not solve for revenue growth in the way that these businesses need. Price increases help, but risk increasing churn. Cash flow is king, as reflected in a recent move by Warner Bros. Discovery: it recently tweaked its executive and employee compensation schemes to reward meeting free cash flow targets.

So, any pursuit of additional business models around the existing database of users seems too risky for existing management even if it is an obvious opportunity for the business model to thrive. The implication being, if there are businesses to be built around an asset like a database of millions of consumers, these legacy media C-suite executives are not inclined to do them.

But macroeconomic headwinds present additional constraints: building businesses requires deploying cash and/or raising cash in the form of debt or equity. Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery and Comcast (owner of NBCUniversal and Peacock) have large debt bills, with Comcast’s at $93 billion in long-term debt. If there are businesses to be built or acquired with shareholder capital or equity, it is more expensive for management to pursue these strategies in a marketplace with high interest rates and low investor enthusiasm for the individual and collective futures of these media companies. The bar is unusually high for management to convince shareholders to deploy capital.

Technology architecture lens

There is an obvious opportunity here, as last year’s “Disney Prime” initiative reflected. Then-CEO Bob Chapek was promising investors that Disney+ would become more than just an app — it would be an “experiential lifestyle platform” for over 150MM Disney streaming subscribers and hundreds of millions more Parks visitors. One credit card on file for a Disney+ account could be monetized within the Disney “flywheel” in multiple ways.

The success of smaller flywheels like Sony’s Crunchyroll and YouTube creators also reflects the opportunity. Crunchyroll is an independently operated joint venture between U.S.-based Sony Pictures Entertainment and Japan’s Aniplex (both part of Tokyo’s Sony Group) that specializes in all things anime. The company makes money through multiple channels: first-party streaming and theatrical releases of new anime content, sales of home entertainment products (e.g. DVD box sets), merchandise licensing, and secondary distribution. The first three of those make up a flywheel and the membership very clearly drives those line items (or CDP business logic).

Meaning, a strategy that starts with a database as the centerpiece of a flywheel seems to require more manpower to build it out than expensive technology acquisitions. That is an important disconnect in the strategies of these large legacy media companies.

Law lens

The question of whether mergers and acquisitions are or should be a strategy for any of these companies has two dimensions to it. There is the technology dimension, above: does acquiring or merging with a smaller competitor improve the odds of a database-driven model?

But there is also the anti-trust legal dimension: Comcast’s or Disney’s potential acquisition strategies are hampered by the risks of a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) suing to block any merger, which seem to be growing by the day. Comcast cannot buy Paramount without spinning out CBS or NBCUniversal because Federal Communications Commission (FCC) rules effectively prohibit a merger between any two of the big four broadcast television networks: ABC, CBS, Fox, and NBC.

The beauty of the Crunchyroll model is that it is too small to attract antitrust attention. The challenge is that other than Netflix, there is no other precedent for a successful execution at a larger scale. Unlike every legacy media company, Netflix was built upon its database of customers and proprietary technology. So any media company pursuing the Crunchyroll as a new model is entering unprecedented territory.

Also, as I argued in January, “it may be true that the skillset for understanding flywheels may be generational and/or related to more technical backgrounds (like [Netflix Co-CEO Greg Peters’), and the older, generation of media executives is more comfortable with sticking with the linear model because it is reliable for cash flow, and it is safer to explain to investors.”

Key Questions

After Netflix’s big livestreaming accomplishment, everything in streaming and traditional media seems both possible and at risk of disappearing. Risk aversion seems to reign supreme as a “better” strategy, both in the marketplace and in keeping investors happy.

Larry Lessig’s “pathetic dot” is valuable because it helps to identify where the constraints in the marketplace still exist. In other words, even where there is uncertainty, being able to identigy where certainty exists helps to identify the key moving pieces.

Arguably the primary key question for the rest of 2023 is whether a change of direction towards a database-driven business is feasible at any streaming service not named Netflix (to remind you, Netflix has pivoted successfully into gaming, ad-supported streaming and livestreaming in the past 24 months). Given that, how are companies constrained from changing direction in ways that Netflix is not?

I think there are three obvious answers that emerge with the “pathetic dot” diagram. Netflix’s competition are constrained in 2023 by:

The marketplace

Technology, and

Legal regulations

The easiest constraints to identify are marketplace constraints. Interest rates are public information as are quarterly and annual public company filings with the SEC.

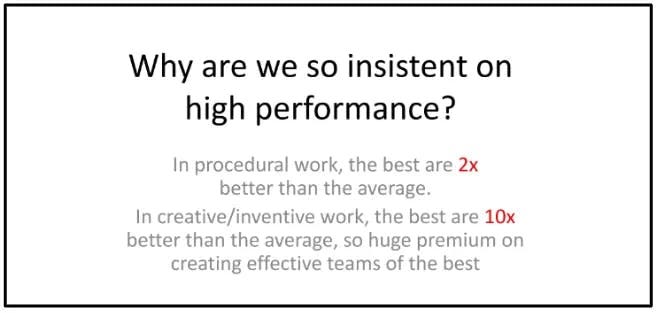

The second easiest to identify but least discussed constraint is technology. The general market assumption is that because the technology for streaming is increasingly being commoditized, the pivot to streaming has been easier for legacy media companies than it was for Netflix to build from the ground up. But Netflix has always and still focuses on the best talent to build the best technology. That remains a moat that commoditization doesn’t solve for. And if you don’t believe that, then why has Disney’s streaming strategy stagnated despite owning both the BAMTech and Hulu platforms?

The most complicated is legal. These companies all face legal and political constraints from the FCC, FTC, SEC and state corporate legal regulations. There is no move these small or large public conglomerates can make without legal scrutiny at the state or federal levels.

The conclusion from all three is that getting bigger — more scale, more cash, more revenues, larger libraries — is the least straightforward solution. But it seems to be the one everyone in the media and the streaming marketplace believes is the most viable.