In Q2 2023, PARQOR will be focusing on three trends. This essay covers "'Media companies have millions of consumer credit cards on file. What are they building for their customers?”

To remind you, PARQOR identifies a few key trends each fiscal quarter that reveal the most important tensions and seismic shifts in the media marketplace. Must-read stories or market developments are not always obvious from press reports or research analysis, and often require a deeper dive. PARQOR’s analysis questions established ideas and common wisdom, reassesses the moving pieces, and reveals the potential in the media marketplace in 2023.

The news of a shareholder lawsuit against Disney was and was not surprising to me.

It was not surprising in the sense that press reports about the surprise firing of CEO Bob Chapek and the surprise return of CEO Robert Iger last year have raised reasonable questions about whether the board and management were acting in the best interests of shareholders when Chapek was CEO.

It was in the sense that the lawsuit does not allege these breaches of fiduciary duty, but rather that Chapek, former Chairman of Disney Media and Entertainment Distribution, and current Chief Financial Officer Christine McCarthy violated securities law with misleading statements about Disney+ and the health of the streaming business.

I doubt this case will go to trial — if Disney is guilty of fraud in its accounting of streaming subscribers, then there is a biblical-style legal reckoning coming for media companies with streaming businesses (and that’s not happening). But if it did, I think the defense teams of Chapek, Daniel and McCarthy would argue that the lawsuit misunderstands Chapek's ambitions for “Disney Prime”. That initiative would have leveraged Disney’s ecosystem and Disney+ membership to boost average revenue per user (ARPU) beyond streaming. But, neither investors nor Disney’s board nor Disney’s management seemed to understand what that meant in practice. Disney’s stock price then fell beneath $87, or 5% lower than where it is now, and shortly after he was ousted.

Putting that aside as a failure of Chapek’s, his initiative mirrored what AMC Networks Executive Chairman James Dolan told investors in Q1 2023: the direct-to-consumer business model requires a “culture change” in these businesses towards “understanding the customer and serving them well”.

Chapek may indeed be right in the long run, despite McCarthy’s rumored dismissal of his model as “cute” and Iger’s dismissal of the model as “marketing”. But in the short run, he encountered a difficult problem: how does a media business go about redefining ARPU in the streaming era? And once they have redefined it, how will they sell it to investors?

Key Takeaway

The growth of streaming and gaming invites a more complicated definition of average revenue per user (ARPU) than past subscription models. There are lessons in how The New York Times is redefining it, and in how Disney and Warner Bros. Discovery are backing away from past efforts to do so.

Total words: 2,600

Total time reading: 10 minutes

Retail vs. Wholesale ARPU

ARPU has long been understood by Wall Street through the lens of the wholesale linear model, where distributors paid licensing fees to broadcast networks. That ARPU is being redefined by the streaming era by the direct-to-consumer model, AMC Networks Chairman James Dolan explained on its Q4 2022 earnings call:

AMC has been a wholesaler, right, as most of the programming companies have been. And in wholesaling, somebody else takes care of the customer, somebody else watches the customer and somebody else actually ends-up pricing to the customer.

When you go to DTC all those things become your responsibility and for an organization to move from wholesaler to retailer is to really significantly change its focus. Things they are paying attention to, things like the customer journey and churn, they are all part of becoming a good retailer.

If we frame Dolan’s points in terms of ARPU, historically linear has had three advantages over streaming:

Linear ARPU is generally higher than streaming,

The consumer relationship is reliable and therefore the revenue is reliable (meaning, minimal churn), and

A third-party (cable networks) is responsible for pricing it.

AMC Networks does not disclose its ARPU, but Lionsgate’s Starz is a similar business . It reported in August 2021 that its a-la-carte ARPU had “started to collide with the OTT ARPU” at somewhere between $5.80 and $6.10 for its domestic business. In May 2022, Lionsgate reported that Starz OTT ARPU had surpassed linear, but projected linear ARPU was $5.75 and $6.05 domestically for the long term. In other words, it is seeing similar revenues in both channels.

Peacock, Hulu & ARPU

We have other available data. In 2020, S&P Global estimated Comcast generates about $6 in ARPU with its bundle of basic cable networks like CNBC, MSNBC, USA, E! and Bravo, and its nine regional sports networks, such as NBC Sports Bay Area and NBC Sports Philadelphia. Adding in advertising revenue from the cable networks, the average cable subscriber's ARPU is closer to $10.

Notably, as of October 2022, Peacock is seeing ARPU close to $10 for paid subscribers. If the majority are ad-supported as recent data from Antenna suggests, they are paying $4.99 per month and therefore making $5 in additional ad revenue per user. So, like Starz, Comcast sees similar ARPU in both channels.

Hulu has similar math, and it is well-known that two-thirds of its subscriber base is on the ad-supported tier. Its SVOD-only tier had ARPU of $11.73 in its FY Q2 2023 earnings.

$11.73 = [.33*($14.99)] + [.67(x)]

$11.73 = $4.95 + .67x

$6.78 = .67x

x = $10.12

This would imply that Hulu was only making an additional $2.13 in ad revenue per user on its $7.99 tier in Q2 2023.

One year ago, it was making an additional $5.17 per user (the ad-supported tier was priced at $6.99 then). In this light, it is worth nothing both Hulu and Peacock are generating similar ad revenues in their ad-supported tiers.

It is also worth adding that, like Disney and Comcast, Netflix makes it easy for investors and observers to deduce ARPU, too. The price of the standard plan is $15.49 per month and the price of the Standard with Ads plan is $6.99. Management wrote in its most recent letter to shareholders its total average revenue per member (subscription + ads), which is their version of ARPU, is greater than its standard plan.”

The implication is that they are seeing ARPU from ads of greater than $9.50 per user, or double both Hulu and Peacock. However, their Upfronts pitch yesterday revealed that was at a significantly smaller scale: 5 million subscribers globally and, if recent Antenna data is any indication, somewhere between 1 million and 2 millions subscribers in the U.S.

Amazon, Apple & ARPU

Amazon and Apple offer streaming services but do not offer investors an ARPU estimate. Neither breaks out their streaming numbers, and instead includes streaming revenues within broader numbers.

Amazon rarely breaks out Prime Video viewership, and instead reports those revenues within its Subscription Services segment, which includes “annual and monthly fees associated with Amazon Prime memberships, as well as digital video, audiobook, digital music, e-book, and other non-AWS subscription services.” It is selective about sharing data on total Prime subscribers (it reported over 200 million worldwide in 2020) and total members who streamed TV and movies in a year (it reported over 175 million in 2021).

Apple lumps TV+ revenues in with its Services line item. That includes Apple’s advertising, AppleCare, cloud, digital content, payment and other services. It has only reported total paid subscriptions for Services, and there were 935 million in Q4 2022. It has yet to break out actual TV+ subscriber numbers.

Neither Apple nor Amazon appears to believe ARPU is a story that improves the story that their basic subscription numbers tell already.

NYT & ARPU

The New York Times is a media business that does share ARPU with investors, and it defines it more broadly than online digital subscriptions.

Its business model is distributing content through digital and print platforms. Its digital platform offers “a digital bundle subscription package that includes access to our digital news product (which includes our news website, NYTimes.com, and mobile applications), The Athletic, and our Cooking, Games and Wirecutter products, as well as standalone digital subscriptions to each of those products and to Audm.” In other words, ARPU is a combination of subscriptions to news, recipes, shopping and gaming.

Its ARPU for these services is presented simply, but the story is complicated.

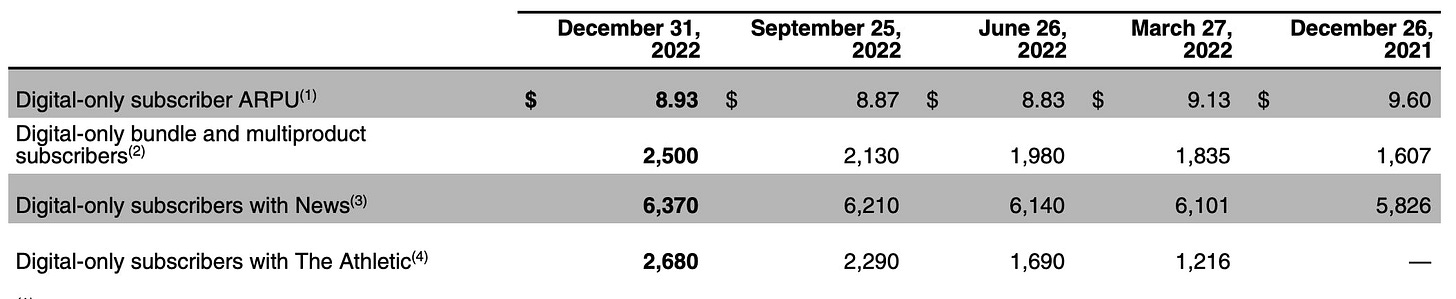

First, it reports ARPU by consolidating digital-only subscriptions to one or more of its news products, The Athletic, or Cooking, Games and Wirecutter products. Management explains in the footnotes that “the final number is the average monthly digital subscription revenue (calculated by dividing digital subscription revenue in the quarter by 3.25 to reflect a 28-day billing cycle) in the measurement period by the average number of digital subscribers during the period.”

In December 2022 its Digital-only subscriber ARPU was $8.93, down from $9.61 in December 2021. But it does not break out ARPU beyond that.

Beneath ARPU it offers three windows into how digital subscribers have signed up:

Subscribers with a digital bundle or paid digital-only subscriptions that includes access to two or more of the Company’s products, including through separate standalone subscriptions.

Subscribers with a paid digital-only subscription that includes the ability to access the Company’s digital news product.

Subscribers with a paid digital-only subscription that includes the ability to access The Athletic.

Its 10-K includes additional tables of total paid digital-only subscriptions but excluding print-only subscribers (8,830), and then digital-only subscriptions where group corporate and group education subscriptions are included (10,260).

These subscriber descriptions are logical — basically, they are a series of conditional statements that reflect how the numbers may be sliced and diced across cohorts of subscriber behaviors —but they also complicate the ARPU story as much as they clarify it.

Chapek’s complicated story

The New York Times 10-K makes it clear why Chapek’s “Disney Prime” vision was a story which generated more uncertainty than enthusiasm from Disney investors. The perks for Disney+ subscribers announced at last year’s D23 Conference are a helpful example of the challenges of this sales pitch:

“Disney+ subscribers will be able to take advantage of a buy two, get two free offer on Disney Cruises, and Walt Disney World will roll out a discount offer for subscribers as well. And on Sept. 8, Disney+ subscribers with tickets to any Disney theme park will be able to enter 30 minutes before they officially open.

Disney is also giving Disney+ subscribers 6 free months of a Net Geo digital subscription for free, and access to an exclusive merchandise portal with Disney goods designed around Disney+ originals.”

From a perspective of a “flywheel” business model, this all reads and sounds incredible. Disney was selling D23 attendees — who are the most passionate Disney fans —that Disney+ was not just a streaming service, but a means of access to deeper and more exclusive engagement with the Disney brands and ecosystem.

But, from the perspective of a single subscription fee, all the upside of this story can get lost easily. In the case of ticket sales to Disney theme parks exclusive to Disney+ subscribers, what is the ARPU? Is it significant enough to matter? How is that different from the ARPU of Disney+ subscribers who purchase merchandise?

The short answer is that it is a complex story, and the easiest solution when dealing with investors displaying growing skittishness about the future of Disney is not to tell that story. And that is effectively what played out for Chapek last November.

Kilar’s Vision

Last March, I highlighted a podcast interview between then-WarnerMedia CEO Jason Kilar and Recode’s Peter Kafka where he laid out the business logic of storytelling in gaming as complementary to storytelling consumed on HBO Max. This explanation from Kilar offers one answer to how a simpler ARPU story could be told:

…if you’re going to invest a lot of upfront capital in creating beloved characters in worlds, I think it’s only natural if you have the capabilities and if you have the skillset in terms of leadership and talent to be able to lean into telling those stories, both in a linear fashion with narrative storytelling but also an interactive fashion with gaming.

He is describing an early version of “Multiversus”, a free-to-play crossover fighting game that had reached over 20MM total players as of August 2022. The game offers in-app purchases and the ability for consumers to fight each other with iconic characters from the Warner Bros. and DC libraries.

The implicit vision of ARPU here is surprisingly simple: gaming and streaming are two different sources of revenue. But, as on Netflix, the user would have one account with WarnerMedia, or perhaps one credit card on file, and WarnerMedia would be able to register usage and revenues across HBO Max and games like Multiversus.

The ARPU in this model would have been an interesting story because the gaming business relies on hits. We learned in the Epic v. Apple trial that high spenders in mobile gaming accounted for less than half a percent of all Apple accounts in 2017 but generated 53.7% of all App Store billings for the quarter, paying in excess of $450 each.

The decision also highlighted that medium spenders were 7.4% of all Apple accounts but spent $15-$450 per quarter and accounted for 41.5% all App Store billing. In other words, streaming would be a recurring revenue story but gaming could offer multiples of revenues as high as 30x HBO Max monthly revenues on top of that. It is a story of marginal ARPU from a small percentage of HBO Max subscribers — 8% if we go by Apple store math — gaming with maximal impact on revenues.

More importantly, Kilar’s ARPU story reflects how consumers are actually behaving now: 9 in 10 Gen Alpha and Gen Z are game enthusiasts, according to recent research from NewZoo, but stream movies and series equally as much. Effectively, this proposed ARPU story would have captured the evolution of a new generation of media consumers, as Kilar implied to Kafka:

...It turns out that a lot of people that [gaming is] their first go-to choice when it comes to entertainment and we happen to be as you also said uniquely positioned, we have thousands of world-class talented game developers, we have a sandbox of IP that people would kill for when it comes to creating incredible immersive worlds we’re doing really well with it and so I happen to be very bullish on it because the consumers are very bullish on it.

The nuanced ARPU of storytelling

Jason Kilar and management of The New York Times management share an ambition to make ARPU more accurately capture digital media consumer behavior. ARPU in digital can be more complicated to capture, so it is an imperfect story. But, The New York Times is telling a story that, as circulation declines, consumers are still spending money within its ecosystem and for more services than news.

This reads a lot like the vision Bob Chapek was trying to implicitly deliver at Disney: as linear and theatrical revenues decline due to the emergence of streaming, Disney+ ARPU could be a proxy for how consumers spend money within the Disney ecosystem. But, the takeaway from Kilar and The New York Times management is that the ARPU story only works if the revenues are digital.

This brings us back to the first question I asked, “How does a media business go about redefining ARPU in the streaming era?”

One answer is that WarnerMedia’s successor Warner Bros. Discovery now has a gaming hit with “Hogwarts Legacy”, an immersive, open-world action role-playing-game set in the world first introduced in the Harry Potter books. However, unlike WarnerMedia it no longer breaks out gaming revenues (around $1 billion per year). Instead, it lumps them with content revenues from film, TV, streaming, sports rights and licensing. This implies they could tell a story of gaming ARPU and streaming ARPU if they wanted to, but for reasons that we can only guess they prefer not to.

As for the second question — “And once they have redefined it, how will they sell it to investors?” — there do not seem to be any good answers yet. The story is still complicated, as the logical complexity of The New York Times data reflects, and investors remain skittish about the future of media.