Member Mailing: The Core Tension/Weird Dance At Upfronts for Connected TV (CTV) Dollars

There is a slide in The Interactive Advertising Bureau’s Brand Disruption 2022 presentation that nicely summarizes the demand side of the upfronts.

The upfronts have historically offered a fixed supply of linear inventory to a fixed demand of buyers: 200 “retail-cartel” advertisers supplying 88% of U.S. network television revenue (the term “retail-cartel” applies to the brick-and-mortar retailers who have historically bought from networks). But recent upfronts addition YouTube now generates more annual revenue ($28.8B in revenues in 2021) than Netflix from a mix of these 200 advertisers and many of the 10MM or so advertisers who buy from Google and Facebook. [1] So, the demand for TV inventory is evolving and is increasingly being shaped by Connected TV (CTV).

Last week’s “The Upfronts Model Isn’t Dead Yet” essay focused more on the supply side dimension of the upfronts equation: what value does traditional linear inventory offer in a world where data and audience targeting are increasingly valued by the demand side?

The deeper story playing out at upfronts was a tension between the persistent demand for linear inventory, and the need for better solutions in addressability (meaning, targeting) and measurement in CTV. 10MM advertisers need the latter - especially those who rely on direct-to-consumer models - while 200 “retail-cartel” advertisers and their media buyers also have that need, but less so.

I think there are three helpful ways to look at that tension:

the upfronts lens

The e-commerce lens, and

The gray area in which Free Ad-Supported TV services (FASTs) and YouTube now sit.

All three reinforce two points I made in a recent mailing, Streamers Hit a Dead-End (Macro) & Consumers Hit Dead-Ends In Streaming (Micro): Discount FASTs (especially Pluto and Tubi) at your own peril, and Discount YouTube as a competitor to legacy media at your own peril.

1. The upfronts lens

Networks lock in as much as 80% of their annual advertising revenues during upfronts week, and eMarketer estimates this year’s linear ad marketplace is $68.4B (and will begin a slow decline after 2022).

In the past, the sales pitch to advertisers was programming (the entire fall schedule) - prime-time viewing and popular shows captured TV audiences at scale, and upfronts offered the opportunity to put a brand next to a show or to a particular A-List talent. The benefit to “retail-media cartel” was access to audiences at scale and there was no market alternative to reaching millions of households on a nightly basis.

The networks managed scarcity and pricing by determining how much inventory they would release upfront (hence, the name), and how much they would withhold for the scatter market (the remaining 20% that could be purchased throughout the rest of the year). It was, and still is, a great model with 74MM households still consuming linear, according to Leichtman Research Group.

But, as I wrote last week, Facebook and Google disrupted that dynamic: “The networks are no longer gatekeepers to scarcity—if audiences aren’t watching TV, they can be found while they’re doing something else like gaming or scrolling social media. Inventory pricing now occurs both annually and in real time.”

2. The e-commerce lens

Facebook and Google have disrupted that dynamic by focusing on servicing what the IAB calls “The Direct Brand Economy” - new direct-to-consumer (DTC) brands with new attributes that leveraged the Internet as the primary channel of reaching consumers and disrupting the “retail-cartel” of brick-and-mortar retailers. The IAB points out that there are eight U.S. cable TV networks with prime-time ratings above 1 million households, but 22,000 YouTube channels with 1 million+ subscribers. Even if it is not a one-to-one comparison, it reinforces the point that networks no longer control scarcity.

The brand managers for those advertisers “get a much more vivid narrative about the efficacy of their dollars from the platforms” than from Nielsen data. Generally speaking, they focus on the Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and Lifetime Value (LTV) of subscribers. But, the more complex game is to increase the reach, segmentation, variability, and complexity of their marketing: These e-commerce brands need a more intimate relationship with the customer than “retail-cartel” brands, and that requires deeper, richer data on the customer across the conversion funnel to both build and maintain that relationship with an eye to both CAC and LTV.

The notable detail about the Upfronts is how, unlike e-commerce brands, retail advertisers were not demanding measurement improvements and alternative “currencies” (meaning, agreed-upon third-party measurement standards) and linear networks did not feel the urgency to deliver them:

“It was interesting to see that while currency was a hot topic of discussion at the NewFronts, it appeared as just a nod during the upfronts,” said Spark Foundry Chief Investment Officer Lisa Giacosa. She noted that there were also few mentions of shoppable ads, which were prominently featured during NewFronts presentations.

YouTube was the only presenter to pitch sophisticated frequency capping controls, which allow advertisers using Google Ads set weekly limits on how often their spots appear to viewers across YouTube and other CTV apps (like Hulu, ESPN+ and Peacock) rather than separately.

3. The gray area in which FASTs & YouTube now sit

The Newfronts are the IAB’s version of the upfronts for the Internet. Rothenberg told me that the Newfronts have been “wildly” successful not because they offer a pricing market around scarcity - because, again, there is no scarcity on the Internet - but rather as an exposure, PR, and information marketplace.

YouTube and FASTs participate in both, creating a confusing gray area for observers trying to distinguish the Upfronts from the Newfronts in this era of growing CTV spend. Both have successful advertising businesses without the Upfronts (programmatic advertising) , and both would benefit from capturing a share of retail’s linear spend, but both are pitching very different buying audiences.

YouTube moved into Upfronts because it now reaches 135MM CTV users in the US. Many, but not all, FASTs present in upfronts because Comcast (Xumo, Peacock), Fox (Tubi) and Paramount Global (Pluto TV) all acquired FASTs that launched with programmatic advertising technology, and now have growing domestic and international scale, too. Other FASTs like The Roku Channel and Amazon’s FreeVee presented at Newfronts this year, though as they scale more that is likely to change.

Consequently, a weird dance played out at Upfronts: networks and YouTube trying to mold a sales pitch to an audience of 200 linear advertisers that was better suited to the 10MM direct-to-consumer advertisers.

As Variety’s Brian Steinberg summed up the dynamic of that approach: “The networks seemed like they were trying to prove they had sheer tonnage more than they did sustainable programming concepts. When you’re trying to match an advertiser’s algorithm, after all, it helps to show you can throw up a lot of content to catch it.”

The core tension/"weird dance"

Steinberg described the Upfront audience as advertisers “armed with data about their most likely customer” telling media outlets to run their commercials based on programmatic technology “that will insert the ad during a particular household’s streaming session or FAST watch, all according to the type of customer they need to entice.”

I think this last phrase “according to the type of customer they need to entice” elegantly sums up the core tension/the weird dance that played out at this year’s Upfronts: CTV offers more sophisticated ad delivery mechanisms for both the 200 retail advertisers and the 10MM e-commerce advertisers.

As Rothenberg recently told me, “Everyone now lives under the same market conditions of abundant, fickle audiences; abundant, wildly varied content; competition from not just three networks but hundreds of companies; and real-time pricing and fulfillment.” But, as we saw above, both groups have very different needs for enticing customers:

Newfronts reflect how e-commerce advertisers leverage CTV and digital video inventory to solve for reach, segmentation, variability, and complexity; and

Upfronts reflect how traditional advertisers say they would like more targeting solutions that CTV offers, but this year’s upfronts also reflected how they do not seem to yet need those solutions.

A recent Innovid/ANA survey reflected how retail brands underweight CTV: the average campaign reached only 13 percent of the available U.S. CTV households (Innovid/ANA estimates there are 75MM), and Innovid/ANA report recommends that upwards of 100 million impressions should be allocated to reach at least 40 percent of the available U.S. CTV population.

But, consumer privacy is increasingly driving both retail brands and e-commerce brands away from digital advertising and towards CTV: 84% of ad buyers told the IAB the consumer privacy issues contributed to the increase in CTVspend.

CTV offers the ability to deliver addressability in a privacy-compliant way at a time where the marketplace - including YouTube - is starting to see headwinds from Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) initiative. In particular, ATT has degraded advertising performance and forced advertisers to scale down ad spend in digital and social.

So, demand for CTV is growing, but there is an open question of which advertisers value it enough to spend what is necessary to succeed.

Conclusion

According to the IAB, CTV ad spend is projected to surpass $14B in 2022.

The adoption of ad-supported tiers by HBO Max, Disney+ and Netflix led The Trade Desk CEO Jeff Green to predict “everyone” will “embrace biddable environments and move away from legacy models, like upfronts and even programmatic-guaranteed, where advertiser choice is limited.” In other words, ad-supported streaming and CTV will drive the world away from the model favored by 200 “retail-cartel” advertisers and more towards the model favored by 10MM e-commerce advertisers.

I highlighted in “The Upfronts Model Isn’t Dead Yet” why this argument missed the continued importance of the Upfronts. But, from a demand-side lens, Green isn’t wrong: CTV serves two different buckets of advertisers on the demand side who mostly, but not always, have very different business objectives. Programmatic software is the common ground between both.

So given this, why are networks struggling to evolve their offerings towards what advertisers need from CTV? There may be a simple explanation: they are not yet incentivized to do so.

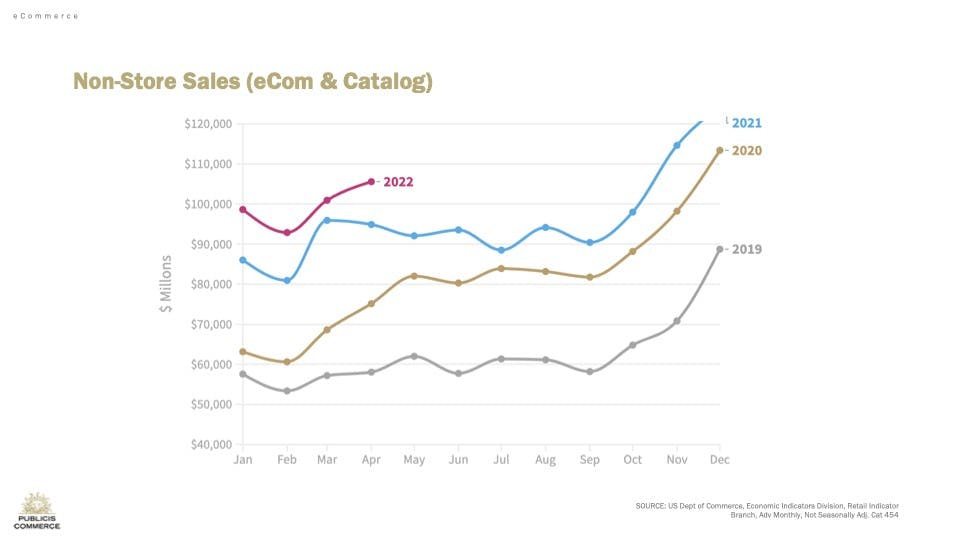

According to a recent Publicis Commerce report, retail was a $6.6T marketplace in the U.S. in 2021 and Publicis estimates e-commerce had roughly a 16% share of the U.S. retail market - a $1T marketplace, or a 6.25x difference. E-commerce’s share of retail is pacing 10% ahead of Publicis forecasts and, before the recent macroeconomic downturn, was seeing monthly sales grow year-over-year.

The 10MM e-commerce retailers may be a smaller marketplace, but they are growing and across channels they are breaking “the century-old retail-media cartel’s lock on the consumer economy”, as the IAB wrote.

YouTube and the FASTs seem best-positioned to capture these advertisers because they already do. Meaning, legacy broadcast networks may have muddied and muddled their pitch about the reach, segmentation and complexity of audiences they can deliver. But, their FASTs do offer the value proposition of programmatic advertising in CTV for e-commerce buyers who increasingly seek to buy it in the post-ATT world. So, YouTube may be an emerging heavyweight for the 200 “retail-cartel” buyers, but FASTs have an increasingly credible story for 10MM e-commerce advertisers. [1]

In other words, discount both YouTube and FASTs at your own peril.

Footnotes

[1] This all points to an open question worth asking: with their enormous domestic (and international) scale, will ad-supported offerings from Disney+, Netflix and HBO Max evolve towards these 10MM e-commerce advertisers? All evidence above suggests there are no easy answers to this question - in some ways, Disney already does because it is building its Disney XP cross-platform ad delivery system off of Hulu’s back-end, and Hulu has historically been the market leader in CTV advertising.

But, to serve those 10MM advertisers, the ad-supported tiers of Disney+ and HBO Max require a level of complexity that wasn’t evident at upfronts, and Netflix is starting from scratch. From the supply-side perspective, it results in a complicated choice of serving an enormous bucket of spend (retail spend on linear) or a growth marketplace that is increasingly disrupting the source of that bucket of spend.