Good afternoon.

The Medium identifies a few key trends each fiscal quarter that reveal the most important tensions and seismic shifts in the media marketplace. The key trends help you answer a simple question: "What's next for media, and where's it all going? How are the pieces lining up for business models to evolve, succeed, or fail?"

Read the three key trends The Medium will be focused on in Q3 2023. This essay focuses on "There is a less-discussed lens on how the demand for “premium content” is being redefined by creators, tech companies and 10 million emerging advertisers."

I closed out Monday’s mailing with a short section on transparency. I neglected to include that one of my predictions for 2023 in my Medium Shift column for The Information focused on transparency: “Ad-supported tiers are black boxes within black boxes within black boxes”. But I also noted how investors “get next to nothing” from legacy media streamers, “making their streaming performance data and finances largely black boxes.”

Eight months later, transparency is a hot topic.

Notably, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and The Screen Actors Guild - American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) have asked for more data transparency from streamers.

Tony Gilroy, director of “Andor” on Disney+, summed up how this plays out for creatives in a recent interview:

One of the central issues of this entire labor experience is that I don’t have any idea what the audience is. We don’t know what that is, and I think that the obscurity of data doesn’t help anyone.

Also, a recent Wall Street Journal article reporting about 80% of Google’s video-ad placements on third-party sites violated promised standards. But as Simulmedia founder and CEO Dave Morgan recently argued, fraud in digital advertising happens not only because there is a lack of transparency, but because “so many folks are making so much money pushing budgets downstream and taking cuts as the money passes them, that the last thing that any of them want is to know where the ad ended up actually running and how many rules were broken in between.”

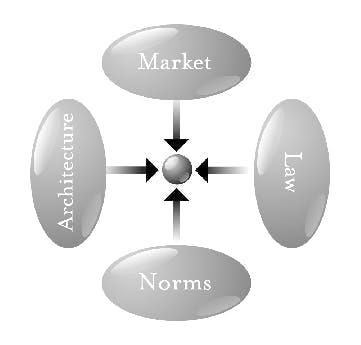

The strikes and The Wall Street Journal article have cast an ethical lens on the transparency of both streamers and digital video advertising platforms. But, I believe it is easier to understand the questions around transparency as less an ethical issue, only, and more as the interplay of a few key factors. [1]

Key Takeaway

It is hard to imagine a lone standard of transparency across streaming and video advertising emerging from these dynamics. It is even harder to imagine a resolution to the demands for transparency in the Hollywood strikes.

Total words: 1,500

Total time reading: 6 minutes

1. Technological

One enormous challenge here is that the data is a function of the technology within the black boxes of Netflix and YouTube. So, data sharing risks reporting on how a show performed *and* how the technology is performing. Netflix and YouTube share some broad-brushed insights into how their respective technologies work via blogs. That is less so the case with legacy media streamers (though Disney offers an infrequently updated blog). But few share much if any data beyond what they decide to share with partners.

All have to walk a fine line: they need to protect their technological intellectual property. Divulge too much, and they have given their competition a new advantage. But divulge too little, and key partners like talent and advertisers are unhappy.

That said, it should be noted that YouTube emphasizes transparency in its relationship with both creators and advertisers, and it has evolved the platform in that direction. That is in large part because creators get 45% of the ad revenues, and 100% of the revenues that they are able to generate on their own. But, a key problem is that Google owns 100% of the data and controls access to it, so even its definition of “transparency” is broader than Netflix's, there is no market competition compelling it to be more transparent with advertisers.

2. Market

Both Netflix and Google (YouTube’s owner) have tightly structured and controlled narratives to tell Wall Street and consumers that their technology is increasingly what audiences use to consume content (Nielsen’s The Gauge is helping to tell this story). To control those narratives, both have to control which data shows up in which people’s hands.

Google’s published blog post response to the WSJ article was a perfect example of this. It basically said that the research report used “irresponsible and faulty methodology” and contradicted findings from independent third parties who monitor campaign effectiveness and safety. In other words, Google controls access to its platform by vetting the methodologies and protocols of partners. It is transparent, but access to its platform is not available to all third parties because not all third parties have responsible methodologies.

Google’s response also mirrors why Netflix and other streamers are less transparent with data: an accurate report is more likely with a vetted partner. “Flawed generalizations and conclusions” are more likely in the hands of someone with an agenda — like a talent agent seeking to get better deal terms for their client — than in a third-party partner who monitors how a show performs. With thousands of shows on its platform, and hundreds being added and removed per year, greater transparency from Netflix increases the risk that someone may take its data, misrepresent its findings and subsequently tank both its relationship with creative talent and its (growing) stock price.

Google continues to be in damage control one month after the WSJ article, even after having disproved the claims with evidence. And Netflix, which is neck-and-neck with YouTube in streaming consumption on TVs, is probably paying close attention.

3. Legal

This is the thorniest lens for understanding transparency. As I wrote last December:

Privacy laws and Apple’s App Tracking Transparency now require companies to protect user data and only share anonymous aggregated data with advertisers in “clean rooms.” Neither party can see the other’s data, so the clean rooms are essentially black boxes. Software, sometimes using artificial intelligence, connects the databases. That means within the black boxes of clean rooms are other black boxes doing the hard work.

Privacy laws impact which data can be shared with partners (and the trend is towards increasingly less data). There are privacy laws at the international level (EU), the federal level and at the state level (California).

But, transparency is also contractual: Netflix sometimes shares data based on agreements with particular studios, and not with others (I broke this down in Monday's essay). Contractually speaking, Netflix's model of upfront payments for original content, and without residuals, effectively tell the creative talent “you bear the risk of producing the content and we bear the risk of the content succeeding, and there is no duty to share whether the content succeeded or not”.

Last, it is worth noting that there is no SEC requirement for Netflix or any public company to disclose viewing data in streaming to investors.

4. Ethical

The arguments from the strikers and Dave Morgan are also ethical. In other words, they believe ethics should fill the void where the market, law, and technology have failed creative talent and advertisers. That is certainly the case Fran Drescher, the actress and SAG-AFTRA President, recently made:

“I have nothing against capitalism. But when you become intoxicated by the money, to the point where you stop feeling respect and compassion for people up and down the ladder, it becomes like a sickness. That’s where I draw the line. And that’s where my members are right now.”

Dave Morgan makes a point with similar logic:

[Marketers] need to care about where their ads are delivered. And, essentially, they must recognize that when they demand “cheaper CPMs” they are telegraphing buyers to dilute their buys with fake stuff and look the other way. It’s that simple. There is only so much real inventory to go around. The markets set prices for it. Hoping to find something dramatically cheaper means that you are begging for goods that are either illusory, fraudulent or likely “fell off the back of a truck.”

Both are describing a problem of ethics on the supply side of a marketplace. Streamers may be “so intoxicated” (Drescher) by Netflix-like scale or programmatic ad platforms may be “stealing money to which they are not entitled” (Morgan). But it's not only ethics: arguing for marketplace participants to find an ethical backbone also reminds them that economic self-interest, at an extreme, can irreparably damage the trust between the supply and demand sides of a marketplace (as IAC Chairman Barry Diller argued recently).

Notably, this is all happening at a time when streaming consumption is trending towards overtaking linear consumption, and when U.S. connected TV (CTV) ad spend is projected to grow 63% between this year and 2027 (per eMarketer).

What happens next?

The issue of transparency is a hot topic for a long list of reasons, some of which are captured by each of the buckets above. I laid out this framework because, for me, it helps me with broad brushstrokes thinking about the problem of transparency.

The most important takeaway may be that consumer demand has changed in ways that Netflix and YouTube understand, some streamers are still trying to understand (especially Disney+, which is seeing growth stagnate), but key market participants do not fully understand yet because they are unable to see the data.

In other words, the Hollywood strikes reflect creative talent betting on a past business model of content creation while blind to evolving consumer behaviors on Netflix and YouTube (and on other streaming services). Whereas, the WSJ article highlighted a marketplace of programmatic advertising platforms who were not blind to fraud, but chose not to care. In one instance the blindness is imposed, and in the latter it is willful. Although the lack of transparency seem like ethical choices in both situations, that lack actually is the result of a wide variety of constraints and incentives created by the technology, the law, the market or the (lack of) ethics in the streaming marketplace, and broadly across both distribution and advertising.

It is hard to imagine a lone standard of transparency across streaming and video advertising emerging from these dynamics. It is even harder to imagine a resolution to the demands for transparency in the Hollywood strikes.

Footnotes

[1] In March I used Larry Lessig's "pathetic dot" to evaluate whether Netflix's mobile games strategy or Epic Games antitrust strategy is better for competing with Apple. I also used it in A Short Essay on “Aggregator Bundling 2.0” & Convergence After Epic v. Apple (available for free on PARQOR's Substack archive), which I wrote in September 2021.