Monday AM Briefing: Content Isn't King Because Culture Is "A Very Shallow Ocean"

In last Friday's mailing, I argued that Disney+ domestic growth of 2MM subscribers via a Hulu Live bundle suggests why marketing - and not content - may be king in streaming:

Disney's "North Star" is also in understanding the types of pricing and other incentives a consumer needs to both sign-up and also not churn out. That is not only a question of content production or content distribution, alone.

In other words, the famous Sumner Redstone adage "content is king"(which, amusingly, Google search results associate with a 1996 Bill Gates essay of the same name) no longer holds true in streaming.

Another angle on how content isn't king emerged in the last 20 minutes of a must-listen interview with journalist and author Chuck Klosterman on the Longform podcast, where he discussed his writing and a recently released book, The Nineties.

Klosterman highlights a cultural argument made by author Mark Fisher that our cultural moment in time suffers from something Fisher describes as "the slow cancellation of the future.” The point is part of a larger philosophical critique of neoliberal capitalism, which I will avoid diving into here.

But his cultural point is about what the meaning of "the slow cancellation of the future" in practice is, as Klosterman explains:

Maybe there's nothing inherently bad about it. But, what it means... it means that everything is to some degree now retro. And that it is impossible because we have such immediate access to the entire history of all art, all political thought, all literature, all of that... it's very difficult to come up with something that is sort of a move beyond what is already there.

He adds a helpful example of movies in the 20th century versus the first two decades of the 21st century:

If we took a clip from an obscure 1965 movie and then another clip from an obscure 1980 movie and you showed somebody who had no understanding of either film, had never seen either film, didn't know any of the performers in it and none of actors... they could still easily tell you which one came first. They could look at it for five seconds. They could listen to them talk for 10 seconds and they would know, "well, this one came in 1965 and this one came in '80. Something has changed."That's not really possible with a movie from 2005 and a movie from 2020. They would appear, they would feel, everything about them would be almost identical. And that's very strange when you think about it.

He also offers a hypothetical of music from 1991 being played to people in 1971. He imagines their reaction would have been, "this isn't music", but music from now played to people 20 years ago and their reaction would be "oh this just came out." He concluded:

It's got to be the Internet. That's the only explanation. In that, instead of moving through culture in a linear way, culture is now more like a very shallow ocean. It's not deep, it's very shallow, and we can access any part of it, and go to any part of this ocean with a bucket and pick up something and there you have "oh, this is what people were doing in the spring of 1994."And as a consequence it is creating this strange static thing.

The Internet originally "seemed like the ultimate accelerant of culture" when it emerged. But, when it became ubiquitous, "it made it so difficult to get beyond the present moment in a creative way."

Now, we find ourselves in "a molasses of cultural thought", where much of culture is driven by nostalgia.

Obviously, I am not a cultural critic so I can't speak to the accuracy of this cultural critique. That said, I do think it is helpful because "the slow cancellation of the future" offers a few implicit and important points about the nature of supply and demand in streaming and the post-"streaming wars" media marketplace.

[Author's Note: The rest of this essay will be exclusive to members, only.]

1. New content = marginal value

First, Klosterman is implying that streaming services - both audio and video - are ultimately more valuable for consuming "retro", past content than newer content. The implication is newer content has some marginal value to streaming consumers. But, in this moment, a streaming service is valued more by consumers for its older content, and that value may be fleeting.

2. Old content = variable marginal value

Second, the reasons for why older content may be more valuable to consumers depend on so many variables. For instance, after actor Charlie Cox appeared in Spider-Man: No Way Home as protagonist Matt Murdock from the Netflix show Daredevil, the show trended to the top of Netflix's top 10 and trending charts, and also to No. 8 on Nielsen’s weekly U.S. streaming chart of originals for the period of Dec. 20-26. But, otherwise, it has not been in discussion for the past three years.

Last week it was announced that Netflix’s license is ending for Marvel’s Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Luke Cage, The Punisher, Iron Fist and The Defenders team-up limited series and the rights to the shows are reverting to Disney.

If their performance on Netflix is precedent, that content will only have marginal value to Disney+ if/when they use characters from those series reappear (as with Kingpin in Hawkeye), and when consumers will be looking for those series in context.

3. Greater content spend ≠ growth

Third, new, original content competes with older content on a platform (something we knew already from Nielsen and Netflix trending and Top 10 lists). So, greater content spend on new content ultimately may not change audience demand for older content on a platform.

The implication is a streaming service library which has a large library of older content over newer content is effectively a utility (e.g., Netflix). Growth will be fleeting because the utility of new content on a platform to past-oriented consumers is fleeting.

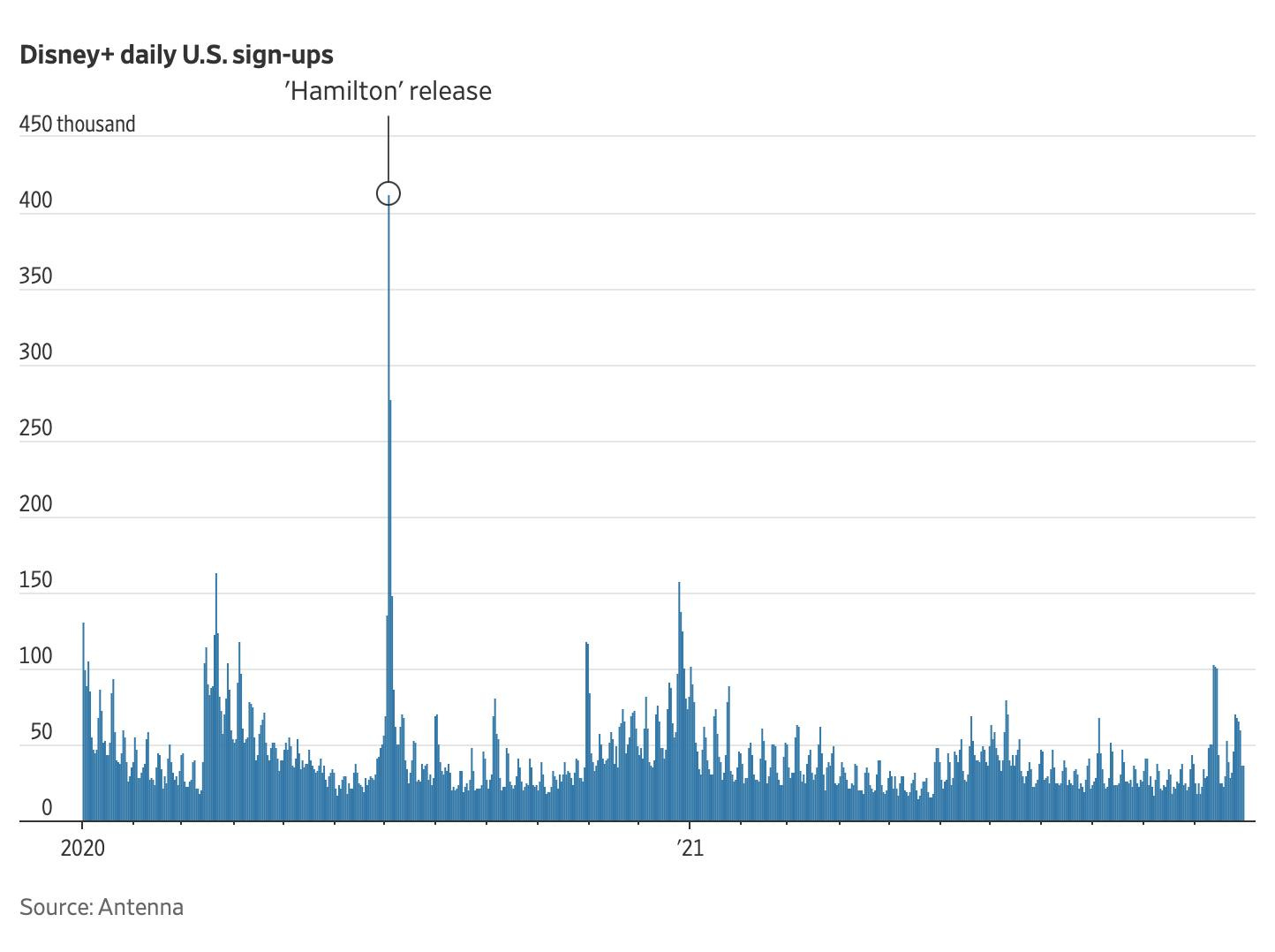

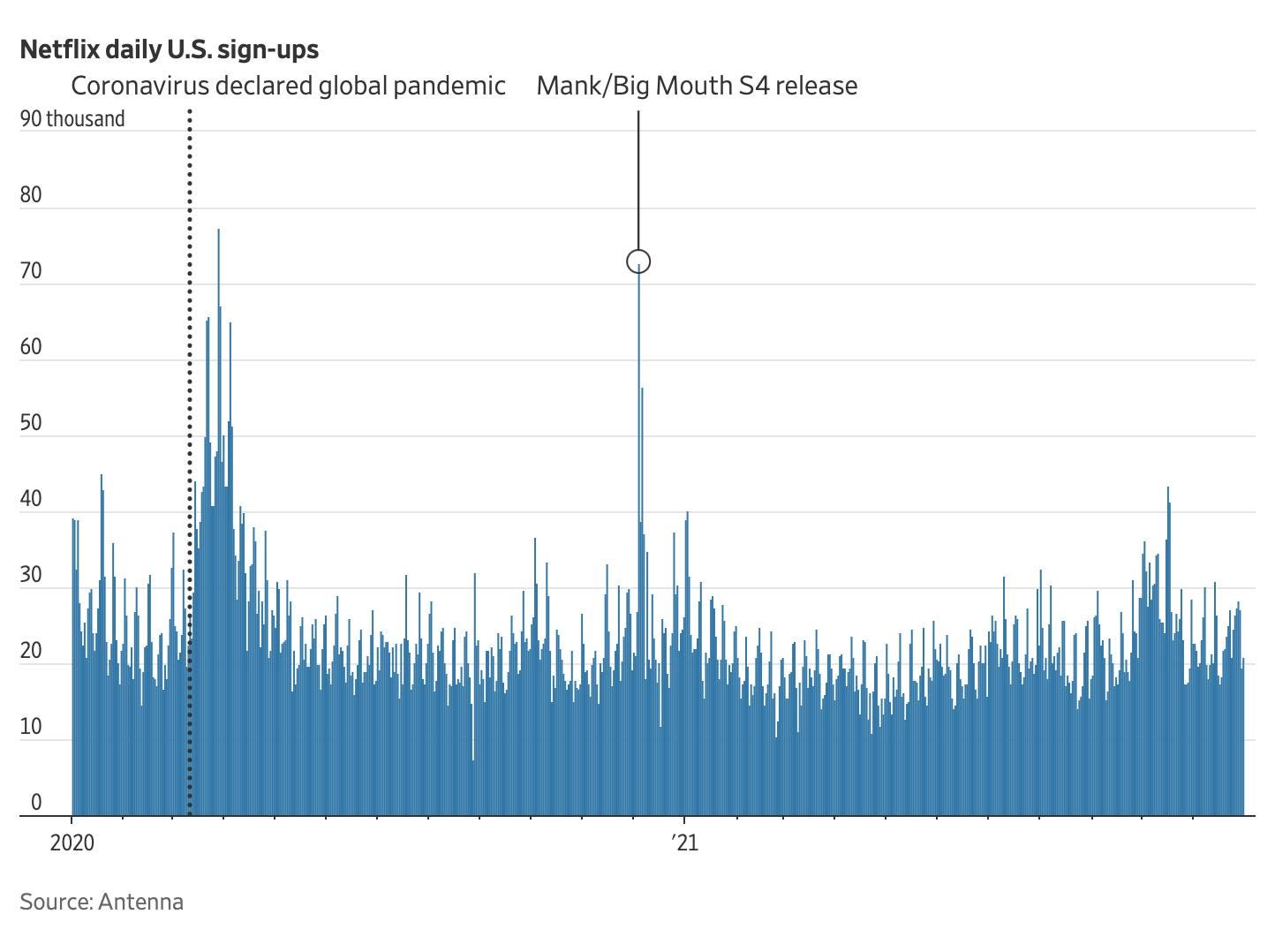

We sort of saw this in a Wall Street Journal report with subscriber-measurement company Antenna that streaming services see a surge of subscribers when they launch a hotly anticipated show or movie, but many of these new customers unsubscribe within a few months.

Meaning, if the intent of larger content spend from Disney, Netflix, Viacom or Warner Bros. Discovery is to drive culture in new and exciting directions, the outcome will be fleeting wins but otherwise subscriber consumption and growth that will be generally slow and steady like "molasses".

All charts provided to the WSJ by Antenna reflected that is already the case (example below).

So where will we find culture?

The logical question from all this is, "so where will we find culture if it isn't on streaming?" Where do we find the movies and series that are moving us "beyond what is already there?" that will make a show's impact last more than a few weeks?

This essay is about supply, so the inevitable place to look is at Netflix, which is spending the most on original content worldwide ($17B and growing), and has ~15,000 titles. But even Netflix has molasses-like growth in the U.S.

So, instead, I think it's worth looking at the recent success of MrBeast's $3.5MM original video $456,000 Squid Game In Real Life, which now has 218MM views (up 4% since I wrote about it in Why YouTube Sees Hollywood’s Future in the Creator Economy).

There are two basic conclusions drawn from 218MM views over three months, and five months after the release of Netflix's Squid Game in September 2021.

First, it tells us that Netflix generates culture, but it needs third-party platforms to fund creators to sustain the momentum of that culture.

Second, MrBeast's Squid Game success suggests that third-party creators may be more important for culture than third-party platforms. Meaning, Squid Game on Netflix arguably has had a longer shelf life than other Netflix content because of MrBeast moved it beyond what is already there.

I am sure there are more sophisticated conclusions to be drawn from more data. The point is, MrBeast's success reflected a spike in additional cultural consumption after a spike in consumption of Squid Game.

In order to push culture in a linear direction, neither Netflix nor any other streamer can do it alone. Creators with models like MrBeast offer a dynamic production model that help content on streaming services "move beyond what is already there".

Must-Read Monday AM Articles

* An argument why Peloton is poised to “ride” a new wave of growth.

* How Peloton can stay independent

Emerging "Metaverse"-type convergence strategies

* Bored Ape Yacht Club members pursuing cannabis deals see the apes as a launching pad for something bigger than even the Yacht Club

* Nintendo’s subscription strategy went from poor to promising with two announcements

Aggregator 2.0

* The Whole Spotify / Joe Rogan Thing Has Absolutely Nothing To Do With Section 230

* An array of movie, merchandising, gaming and live event rights to “Lord of the Rings,” “The Hobbit” and other titles from author J.R.R. Tolkien are coming up for auction and are expected to fetch at least $2B

Sports & Streaming

* International rights for the Premier League will hit £5.05 billion, while UK broadcast rights will be worth £5 billion between 2022 and 2025. ($ - paywalled)

Creative Talent & Transparency in Streaming

* Business Insider profiled Spotter, which has spent $330 million to purchase the rights to YouTube back catalogs in exchange for 100% of those videos' advertising revenue. ($ - paywalled)

* How to be a TikTok music megastar

* Matt Koval, YouTube’s first creator liaison, is leaving to become senior vice president of creators for Mighty Networks, a subscription-based service for creators to run online courses, memberships and events.

* Moonbug Entertainment is acquiring Little Angel, a YouTube network with more than 88 million subscribers. Like Cocomelon, Little Angel uses 3D animation and original songs to entertain children.

Original Content & “Genre Wars”

* Marvel's Kevin Feige told Empire magazine in an interview that "the boundaries shifting on what we’re able to do" with Disney+, and Moon Knight will reflect "a tonal shift" in its embrace of violence.

* The sudden departure of CNN Head Jeff Zucker "throws a wrench" into the WarnerMedia's plans for CNN+

* Variety's Brian Steinberg went behind-the-scenes of ESPN's success with the ManningCast

Comcast’s & ViacomCBS’s Struggles in Streaming

* NBCU executives are spinning the Olympics as a net positive for Peacock, despite poor ratings, but then again, maybe hasn't been a net positive.

AVOD & Connected TV Marketplace

* A report from Fox's Tubi and data from research firm MarketCast says SVOD audiences grew by 8% in 2021, while AVOD increased by 16%.

* YouTube's Chief Product Officer Neal Mohan previewed a redesign of YouTube TV on the YouTube blog. He also spoke with The Verge editor-in-chief Nilay Patel and streaming reporter Catie Keck

* Mike Shields asks, "Could Netflix realistically sell $100 million in advertising the US?"

Other

* The U.S. subscription streaming business expanded by nearly 20% in 2021, reaching $25.3 billion, according to figures published Monday by Digital Entertainment Group (DEG).

* MoviePass reemerged with a blockchain-based model

* Disney+ carried a livestream of the Academy Awards nominations announcement.

* The Economist asked, Is Anyone Winning The Streaming Wars?, and What's On Netflix's Kasey Moore asked a group of writers and former executives "How Can Netflix Keep Its Streaming Crown?"