Monday AM Briefing: Is Netflix's Mobile Games Strategy or Epic Games Antitrust Strategy Better vs. Apple?

Last September I wrote A Short Essay on “Aggregator Bundling 2.0” & Convergence After Epic v. Apple (available for free on PARQOR's Substack archive).

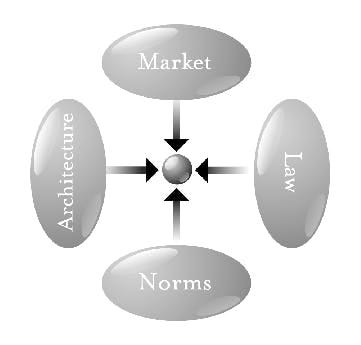

That essay used Larry Lessig's "pathetic dot" to explain why Apple's App Store and iOS software were not a problem of antitrust law. Instead, in "pathetic dot" terms, Apple’s regulation of the App Store Marketplace (✅ Market Dot), and Apple’s proprietary technological architecture for that Marketplace (✅ Architecture Dot) resulted in anti-competitive behavior that did not meet the definition of a monopoly under antitrust law (❌ Legal Dot).

In last Friday's mailing, I asked whether Netflix's acquisition of Boss Fight Entertainment implied it may be taking steps towards becoming an Apple App Store and Google Play competitor in mobile gaming.

The "pathetic dot", above, suggests Netflix may offer a better solution for the mobile gaming marketplace than Epic CEO Tim Sweeney has been arguing for.

Epic's lawsuit focused on Apple's "monopolistic practices" within iOS and also within payment processing for the App Store: Apple takes both 30% of every sale of every app, and 30% of in-app transactions, too. Epic argued:

Apple imposes unreasonable and unlawful restraints to completely monopolize both markets and prevent software developers from reaching the over one billion users of its mobile devices (e.g., iPhone and iPad) unless they go through a single store controlled by Apple, the App Store, where Apple exacts an oppressive 30% tax on the sale of every app. Apple also requires software developers who wish to sell digital in-app content to those consumers to use a single payment processing option offered by Apple, In-App Purchase, which likewise carries a 30% tax.

One set of questions before the court was how Apple's practices impacted third-party gaming developers as big as Epic, and smaller third-party gaming developers, too.

There is no single section devoted to the impact of Apple's practices on small developers in the ruling from Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers. So, for the sake of this essay, I'm going to focus on the angles that relate to the "creating delightful game play without worrying about monetization" line in Netflix's Boss Fight Entertainment press release.

Because that raises two questions:

What does the Epic v Apple decision tell us about why a smaller games developer would say they worry about monetization? And,

What solution is Netflix offering here that Epic Games is not?

Small games developers & monetization

It's worth reviewing how the findings of fact in Epic v Apple described the business model for smaller games developers on the App Store.

Judge Gonzalez Rogers found the App Store "provides many benefits to developers, including developer tools, promotional support, and a ready audience, that enables small developers to compete with large ones." In particular, "72% of small developers lack a marketing budget, and Apple provides significant free advertising and “spotlighting” to help users discover new apps as part of its DPLA".

But the key finding of fact was about spend and how "game apps are disproportionately likely to use in-app purchases for monetization":

Games have played an integral part of the App Store since at least 2016. In 2016 for instance, despite game apps only accounting for approximately 33% of all app downloads, game apps nonetheless accounted for 81% of all app store billings that year. Further, based on Apple’s internal records, 2017 gaming revenues overall accounted for 76% of Apple’s App Store revenues. These commissions are substantially higher than average due to the prevalent and lucrative business model employed by most game developers. Specifically, game apps are disproportionately likely to use in-app purchases for monetization.

Importantly, spending on the consumer side is also primarily concentrated on a narrow subset of consumers: namely, exorbitantly high spending gamers. In the third quarter of 2017, high spenders, accounting for less than half a percent of all Apple accounts, spent a “vast majority of their spend[] in games via IAP” and generated 53.7% of all App Store billings for the quarter, paying in excess of $450 each. In that same quarter, medium spenders ($15- $450/quarter) and low spenders (<$15/quarter), constituting 7.4% and 10.8% of all Apple accounts, accounted for 41.5% and 4.9% of all App Store billing, respectively. The remaining 81.4% of all Apple accounts spent nothing and account for zero percent of the App Store billings for the quarter. The trend has largely continued to the present.

This trend is also mirrored within the App Store’s games billings. Indeed, Apple has recognized that “[g]ame spend is highly concentrated” among certain gaming consumers. Similar to the above statistics, 6% of App Store gaming customers in 2017 accounted for 88% of all App Store game billings and were gamers who spent in excess of $750 annually.

All of this suggests that, probabilistically speaking, smaller developers must rely on the App Store and Google Play Store to reach consumers. But, they face challenges in finding consumers who will spend more than $15 per quarter. Scale is hard because the competition is fierce, mobile gaming is a $100B market and success seems to be unfairly penalized by a 30% revenue share.

Netflix's Solution vs. Epic Games' Solution

Epic Games positioned itself as a white knight for smaller developers with its Epic Games Store, which "uses a commission model and markets an 88/12 split of all revenues to developers from the sale of their games." The 88/12 commission is "a below-cost price and the store is expected to operate at a loss for many years at this rate."

The decision adds:

Epic Games acknowledges that its commission is not merely a “payment processing” fee. The 12 percent fee is principally for access to Epic Games’ customers, but also is intended to cover all of Epic Games’ variable operating costs associated with selling incremental games to customers. It covers various services to game developers, including “hosting, player support, marketing of their games, and handling of refunds,” “a supporter/creator marketing program,” and “social media for game launches, video promotions[,] . . . featuring at physical events, such as E3[,] [a]nd sponsorships of the video games.” The commission is thus “tied into these broader ecosystem benefits that [Epic Games] provide[s] to [its] developers,” and is intended to cover the full “cost of operating the service,” “the actual distribution cost, the internet bandwidth cost, [and] the . . . cost of maintaining it.”

Epic Games Store has over 180 million registered accounts and more than 50 million monthly active users. It supports more than 100 third-party app developers and publishes over 400 of their apps

In effect, it is charging 12% to access these 180MM registered accounts, and there seems to be an implicit opportunity to further reach 400MM Fortnite users. The purpose of its lawsuit to force Apple to distribute its Epic Games Store without charging Epic and its developers an additional 30%, and to allow Epic and its developers to use their own payment processing platforms.

That lawsuit failed, as Gonzalez Rogers concluded these problems may not reflect monopolistic control over the broader mobile marketplace or narrower mobile gaming marketplace (❌ Law Dot). Rather, it may reflect anti-competitive behavior emerging as a result of the software of that marketplace (✅ Architecture Dot, ✅ Marketplace Dot).

Netflix's Model

As of now, Netflix does not seem to be bringing to the market anything remotely similar to the Epic Games Store. It has bought three developers (Boss Fight Entertainment, Next Games (March 2022), and Night School Studio (September 2021)).

It has 220MM subscribers, and it seems to be focused on creating games based on IP it owns. But, as I argued last Friday, Netflix may see a business opportunity in aiding developers who also seek to create "delightful game play" and are objectively penalized by the marketplace dynamics and limited monetization tools offered by the App Store.

Netflix has not created a store, nor an in-app payments platform (❌ Marketplace Dot). Rather, it is narrowly focusing on distributing games to its mobile users, only, as part of their subscription (✅ Architecture Dot). In turn, that does not violate the terms of distribution on the App Store and Google Play Store (✅ Law Dot). It is doing so with first-party apps, analogous to Apple's early days with its own App Store.

Everything seems entirely precedented and the decision does not seem to driven by any ethical concern for the App Store's 30% fee, which Netflix has not paid for new subscribers since 2019 (❌ Moral Dot). This is unlike Epic's legal case which framed itself in broad, moralistic terms like “consumer freedom” and “fair competition” (✅ Moral Dot).

Instead, Netflix's objective seems to be to leverage its scale and software platform to enable gaming distributors to create "delightful game play without worrying about monetization" (✅ Architecture Dot, ✅ Marketplace Dot).

It can continue to offer "no ads and no in-app purchases" for now and for the foreseeable future without any concerns from Apple. [1] In turn, Netflix can start partnering with third-party games developers, and offering a variable cost revenue sharing model similar to the one it third-party production companies.

However, Apple still controls the contractual terms for the App Store. Given that 88% of all App Store game billings are gaming customers mobile gaming is a $100B marketplace, and Netflix is not sharing revenues for new subscribers via the App Store, Apple still holds a very powerful Law Dot card here.

It doesn't seem poised to play it anytime soon. But, Netflix seems to coming for Apple's weak spot in a $100B marketplace, and at a time when it needs to show investors growth. Unlike Epic Games, it doesn't need law because it has scale ( (✅ Marketplace Dot) and "ubiquitous access" for marketing gamings both on-platform and off-platform ( (✅ Architecture Dot).

For that reason, it seems like has pinpointed two real weaknesses in Apple's model that Epic Games' failed lawsuit missed.

Footnotes

[1] Although Apple will not benefit from new sign-ups, it will benefit from reduced churn from Netflix subscribers who signed up in December 2019 and before)